Most people understand the daily and weekly weather forecasts that we use regularly to plan our lives. Will we go for a walk or is it going to rain? Do we need to bring those plants inside before the ground starts to freeze? When is it going to be hot and sunny so we can plan a holiday?

However, the daily and weekly weather forecasts are only one part of the monitoring undertake by meteorological organisations. There are also longer patterns in our climate and weather that are monitored and forecasts made for months ahead, letting us know how severe a winter might be, or how dry the summer. Perhaps one of the most famous examples of these seasonal forecasts is the El Niño/La Niña forecast. Many people have heard of either El Niño or La Niña, but it is not very well understood.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO is a particular pattern of ocean currents that occurs in the Pacific Ocean and affects weather all over the globe for months at a time. It is of particular importance when looking at the severity of winter in the northern hemisphere.

What exactly is ENSO, though? How does an ocean current affect climate?

The basics of ocean currents

Ocean currents are found all across the globe. They are not just the lifeblood of our oceans, carrying heat and nutrients, but also play a huge part in our climate.

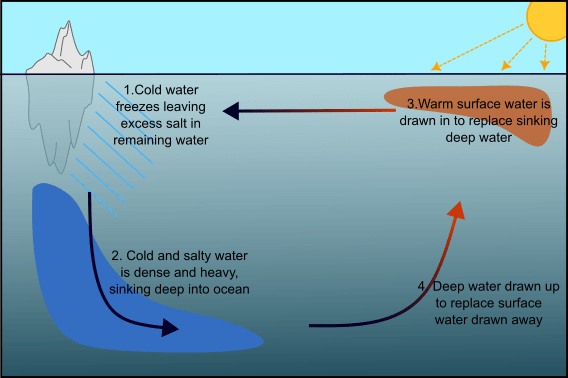

Ocean currents are driven primarily by three major factors. The first is heating. Just like air, water becomes dense and heavy when it is cold and less dense and lighter when it is warm. As the ocean is heated unevenly across the globe, there are areas where ocean water is colder and sinks down below warm water. Just like with air, if water sinks in one area and rises in another, this creates a pull between the two areas to fill in the space left behind.

The second factor affecting currents is salinity or how much salt is in the ocean water. Warm water can hold more salt and is often saltier because where the ocean is heated some water evaporates leaving salt behind. In rare situations this can cause warm water to become as dense as cold water. However, there are also cases where cold water can become excessively salty. This happens primarily in the Arctic and Antarctic where sea ice forms. As the water gets colder, it begins to freeze, however the salt does not freeze and instead is left behind. This creates very dense, very cold water which sinks below all the other water.

The third and final factor is wind. There are winds, such as the Trade Winds, which blow consistently in one direction for long periods of time. This can cause water at the surface of the ocean to be pushed in the same direction as the wind is blowing. These surface currents are weaker than the currents driven by temperature and salinity, but can have a big effect because they can cause cold water from deep down in the ocean to be pulled up to the surface against the normal pattern of cold water sinking.

The cycle of El Niño/La Niña is a cycle that is primarily driven by the third of these factors – the strength of the Trade Winds.

The Trade Winds

As we discussed in our article ‘Climate change will make the monsoonmore extreme: but why?’, at the equator the weather is primarily controlled by the Hadley Cell, a circulation of air driven by excess heating at the equator. Hot air rises at the equator, moves north and south as it cools and then sinks back to the ground close to the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. The Trade Winds then carry air back from the tropics to the equator.

This means the Trade Winds are some of the strongest and most consistent winds on Earth, blowing almost continuously. The strength of the Trade Winds can vary, as they are dependent on how much heating is occurring around the equator and tropics, but generally they will always be blowing to some extent and always in the same direction.

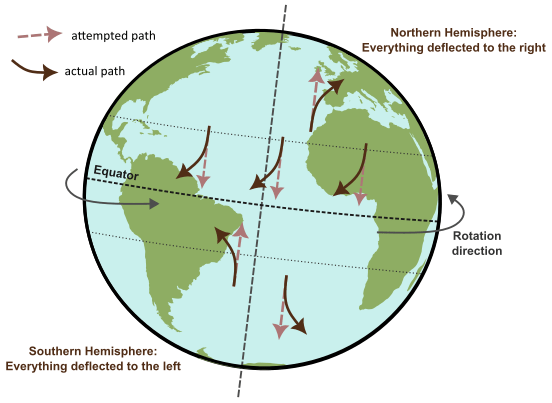

Due to the Hadley Cell, we would expect the Trade Winds to blow purely north or south, depending on which side of the equator they are on. However, the direction of the winds is also affected by the rotation of the Earth.

In simple terms, if you try to travel across a spinning disk in a straight line, you will find it is very difficult to do. As the disk spins, you are naturally dragged slightly to one side: if the disk is spinning clockwise, you will veer slightly to the left, if it is spinning anti-clockwise you will veer slightly to the right. To walk straight you have to actually walk at an angle. This is called the Coriolis Force and it also affects everything on Earth.

Of course, because of the size of Earth and how fast it spins, it is difficult to see the Coriolis Force in action in most situations. It is easiest to see when you look at the path that hurricanes and other tropical storms take – they will follow a curved path which turns to the right or left depending on which hemisphere they are in. However, the Coriolis Force affects everything to some degree including the Trade Winds.

North of the equator the Trade Winds try to blow south, towards the equator, but are then deflected to the right i.e. they are deflected westwards, following the equator.

South of the equator the Trade Winds try to blow north, again towards the equator, but are then deflected to the left i.e. they are also deflected westwards, following the equator.

The Trade Winds, therefore, consistently blow westwards regardless of whether you are in the northern or southern hemisphere. We can use this to understand what happens to the ocean currents in the Pacific Ocean.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation

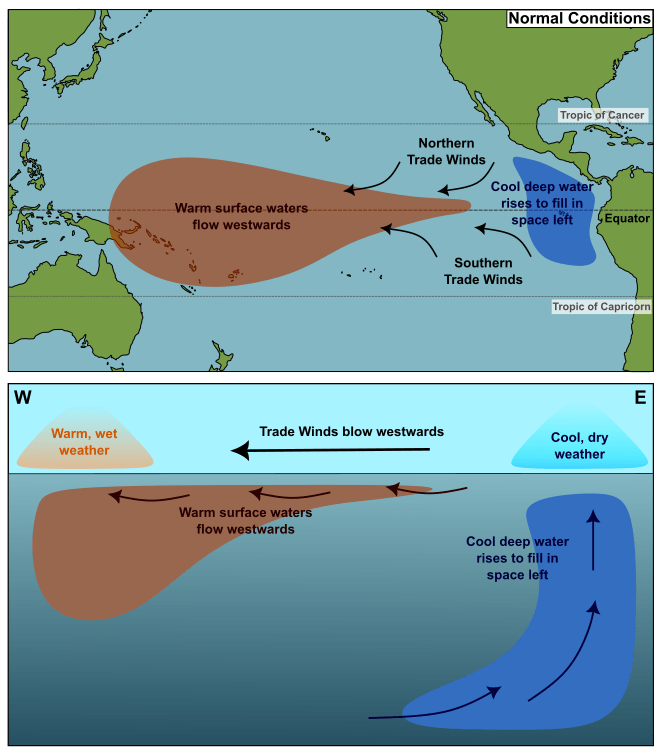

The equatorial region of the Pacific Ocean stretches from the south-western US and central America in the east to the Indonesian islands and Philippines in the west. As with all regions around the equator it is warmed by the large amounts of sunlight it receives throughout the year. However, because of the huge stretch of ocean, uninterrupted by land, it means that the Trade Winds have a big effect on the surface of the ocean.

Off the coast of America, water close to the surface is warmed by the sun, but then steadily pushed westwards by the consistent Trade Winds. As it flows westwards it continues to warm until it reaches the western side of the Pacific. This warm surface water builds up in the western Pacific, leading it to be warmer than it should be, based on heating from the sun alone. Warm oceans create warm, humid spots in the air and these tend to lead to wetter weather.

The removal of this surface water in the eastern Pacific leaves a space that needs to be filled. Cold water from deep down in the ocean is dragged upwards. This creates an area around the south-western US and central America that is much cooler than it should be. Cooler oceans mean cooler air and cool air tends to lead to drier weather.

This is the typical climate for the Pacific Ocean and would be considered ‘normal’ weather. However, as previously mentioned, the Trade Winds do vary in strength year-on-year and this leads to changes to the ‘normal’ state of the Pacific Ocean. The change from the ‘normal’ state appears to follow a cycle which lasts somewhere between 3 and 7 years where it varies from normal conditions to La Niña or El Niño conditions and back again.

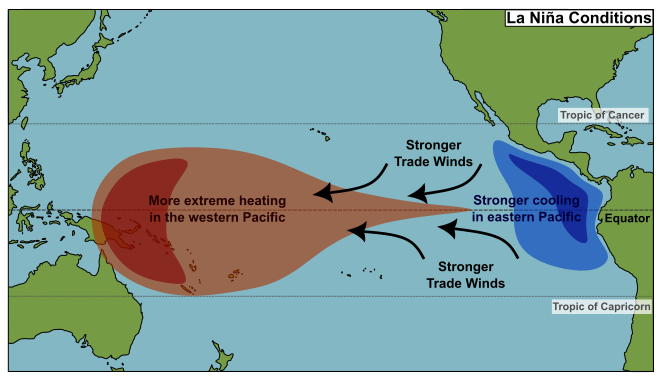

A La Niña event is easier to explain, as it is basically the normal state but stronger. La Niña events occur when the Trade Winds strengthen. This means the surface current from the eastern Pacific to the western Pacific is stronger. More heat is concentrated around the Indonesian islands and the Philippines while cooler conditions persist around the south-western US and central America. La Niña can lead to droughts in the east and more tropical storms in the west, because of the knock-on effect of cooler or warmer temperatures.

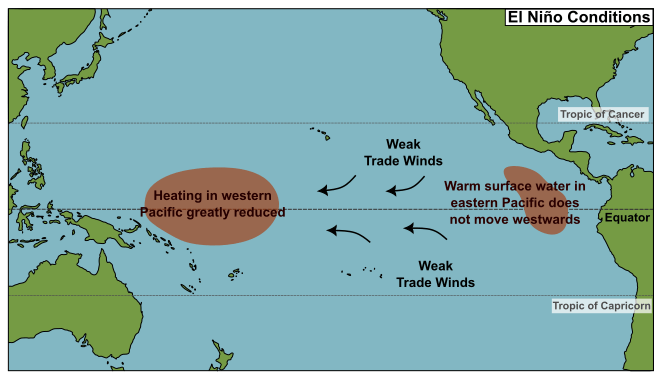

In comparison, an El Niño event occurs when the Trade Winds weaken. As the winds are not blowing as strongly, less surface water is pushed westwards, reducing the amount of heat transferred from east to west. It also means that there is less pull on the cold water from the deep ocean and so it does not rise to the surface. The eastern Pacific gets warmer and wetter weather, while the western Pacific sees cooler and drier weather.

An El Niño or La Niña event will last for months or even years, depending on the severity, before returning to a more ‘normal’ state, affecting weather the entire time.

Now this is all very interesting, but, you ask, how do we go from weather in the Pacific to weather across the globe? Can this cycle really control weather even in Europe, despite being on the other side of the world?

In short, yes.

How does ENSO affect Europe?

All parts of the climate system, as well as the ocean and air circulations systems, on Earth are interconnected. A change in one will affect another, no matter how far away it is. How big the effect is, varies, but large cyclic changes such as the ENSO are relatively easy to track.

During an El Niño event Europe tends to have colder winters with most winter storms being pushed southwards of their usual paths. Although the exact mechanism which connects the Pacific to Europe is complicated it comes down mainly to circulation in the atmosphere.

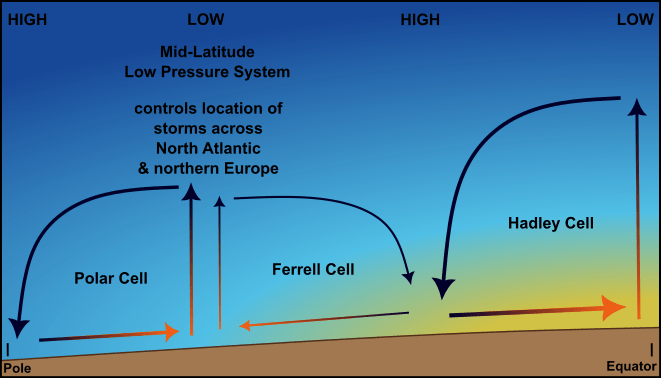

The Hadley Cell, which we have discussed before, is one of three major air cells: the Hadley Cell, the Polar Cell and the Ferrell Cell which cover the globe between the equator and each pole. Each cell has a northern and southern part to it and they work in the same way in each hemisphere. The Hadley Cell, we know, is driven by unequal heating at the equator compared to the tropics. The Polar Cell works in a similar way. There is very little heating over the north and south poles while some heating still occurs in the regions between the tropics and the Arctic or Antarctic circles. This region is called the mid-latitudes (between 25° to 65° N or S).

In the Polar Cell warmer air rises in the mid-latitudes and sinks over the poles. The rising air in the mid-latitudes creates an area of low pressure at the surface, while it carries water up into the atmosphere to condense into clouds and form storms. At the poles, sinking air creates higher pressure and reduces cloud formation, reducing the number of storms.

The Ferrell Cell, on the other hand, is not so much driven by heating as it is by the movement of air in the Hadley and Polar cells. Around the tropics, air is descending along one side of the Hadley cell, while in the mid-latitudes air is rising on one side of the Polar Cell. The Ferrell Cell in between these two sides is forced to follow this same air circulation. This means, however, that any changes in the Hadley cell have a knock-on effect onto the Ferrell Cell, which causes changes in the mid-latitudes.

During an El Niño event, when the Trade Winds are reduced, we see that the knock-on effect to the Ferrell Cell causes more air to rise over the mid-latitudes. This rising air creates a stronger low pressure and more storms.

In Europe, the low-pressure region is also shifted southwards, as well as being stronger. This means that winter storms happen further south than usual. Also, as these storms pull winds in to them, anywhere north of the storms will experience cold air from the poles being drawn further south, resulting in colder weather.

Will climate change affect ENSO?

The final question, then, is will the current trend of changing climate due to global warming affect the cycle of ENSO? We do know that under a warming climate, we will see more extremes of weather – both more storms and droughts – than we currently see. It would follow then, that we would expect the El Niño/La Niña cycle to become more intense. To see longer and stronger La Niña and El Niño events.

However, ENSO is a very complex system which we cannot yet fully model and, in truth, we don’t actually know how it is going to react to climate change. Scientists see no strong evidence to suggest it won’t follow the same patterns we are seeing elsewhere in the climate – of increasing intensity – and plenty of reasons to think it will, based on the underlying physical processes. Yet, there are many unanswered questions and problems associated with the climate models used.

The 2020 book ‘El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate’ published by the American Geophysical Union goes into much more details on the limitations of our current knowledge and projections. However, models are improving constantly and much progress has been made in answering this question over the last ten years. It won’t be long before we have a much more conclusive answer as to what will happen to ENSO and the associated weather patterns in the future.

Leave a comment