Solar panels are a well-established green technology in many places. For many years now, they have been used as a primary example of how an individual can both decrease their carbon footprint and their energy bills. If you could afford to buy one, supporters insist, they will pay for themselves in just a few years.

At the same time, however, critics are quick to point out their expense, their lack of efficiency and how they stop working when it gets too hot.

Obviously, there are going to be advantages and disadvantages for any piece of technology and solar panels are no different. How, though, do we know whether the benefits outweigh the costs? Are solar panels truly worth the investment, or is it just a way for companies to sell us expensive pieces of technology that don’t meet our needs? To answer this, let’s start with the basics of how solar panels work.

Generating electricity from sunlight

There are two major types of solar power – concentrating solar-thermal and photovoltaic. They both use sunlight to generate power, but do it in different ways. Concentrating solar-thermal power uses sunlight to heat water, which can then be used as hot water, or used to drive turbines to generate electricity. This is more commonly used now for industrial purposes, so we will be focusing more on the other type of solar power, photovoltaic.

Photovoltaic (PV) solar power is the version most people are familiar with and is used in the majority of household solar panels. With PV power electricity is generated directly from sunlight.

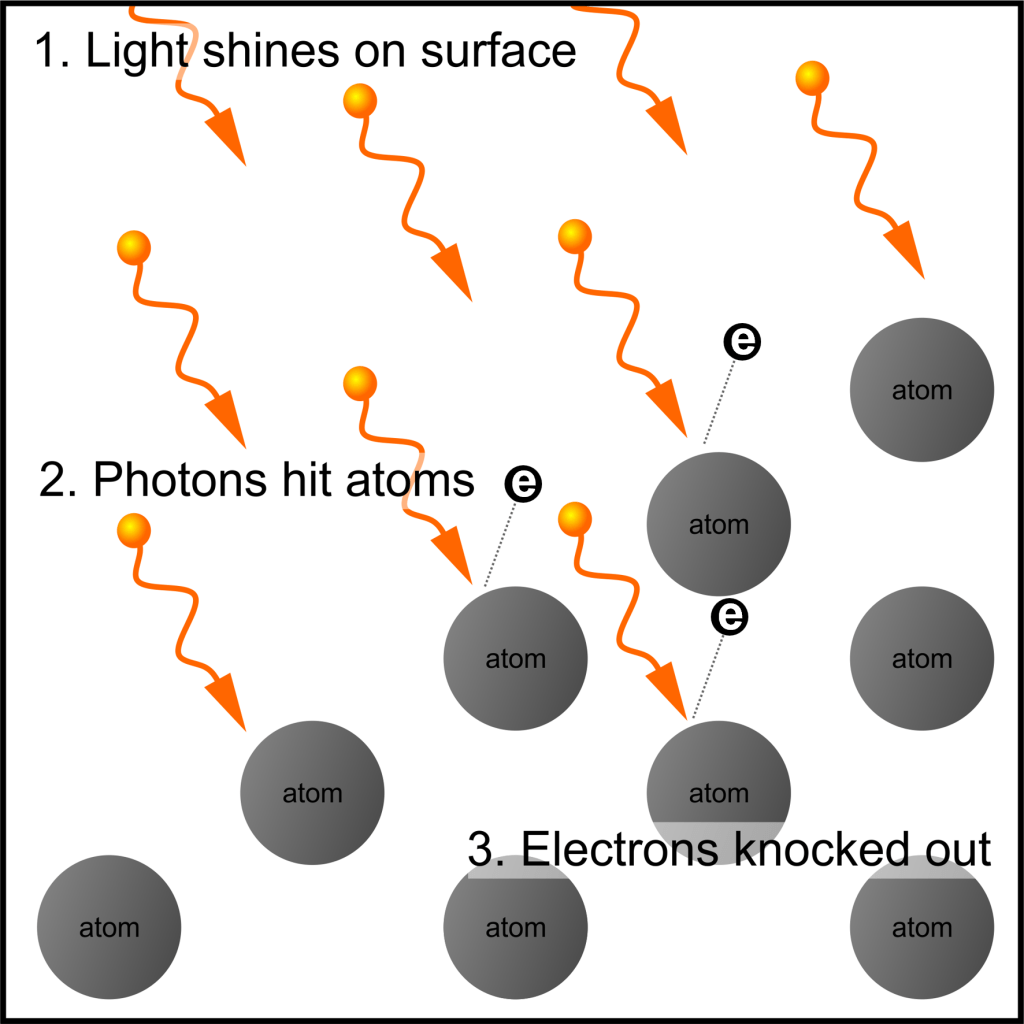

PV power relies on a relatively simple reaction that occurs when sunlight hits certain materials. You may be surprised to learn that light is not, technically, just energy – a beam of light contains tiny particles called photons as well as energy. These photons are smaller even than atoms and can pass right through the spaces between atoms, so they don’t often affect other material themselves.

However, occasionally, the photon will hit an electron – one of the three things that make up atoms – and knock it out of the atom. This doesn’t happen very often, because electrons are always moving around. However, in the context of billions of atoms that make up any given object and the millions of photons that are hitting an object every minute, a lot of electrons can be knocked out of position.

This reaction, where light hits an object and electrons are knocked out of position, is called a photovoltaic reaction. This is a reaction we’ve known about for hundreds of years and use widely in a lot of different ways – for example, before digital cameras, photographs relied on PV reactions to make pictures. The key to solar power, however, is making use of those free electrons to generate electricity.

We have discussed before that nature likes things to be in balance and for things to be distributed evenly. This can be heat and energy or it can be a material like salt in water. It also applies to free electrons that have been knocked out of place by photons. The electrons flow to create an even distribution. As electricity is, quite simply, the flow of free electrons through a circuit this is how solar panels use the PV reaction to generate electricity.

Structure of a PV panel

A single PV cell is made up of two layers of a semi-conductor. That is a material that can allow some electricity to pass through it, but not quite as freely as in a conductor such as metal. The most common semi-conductor used is silicon.

The top layer of silicon will be made in such a way that it has excess electrons – more than silicon would naturally have. The bottom layer of silicon is made depleted of electrons – less than it naturally has. This creates a gradient between the two layers. When the top layer of silicon is hit by light, photons knock electrons free and they naturally start to move towards the bottom layer. This starts the flow, but, on its own isn’t enough to generate a lot of electricity. This is because as the electrons move between the two layers, the gradient would eventually even out. You need something to draw electrons away from the bottom layer and add them back to the top layer.

The layers are therefore sandwiched between two layers of metal bands, which are in turn connected to a complete electrical circuit i.e. the household electrical grid. Electrons flow from the top layer of the silicon into the bottom layer, then from there into the circuit before being fed back into the top layer via the metal banding. This creates a closed loop and allows for an electrical current to form.

A single PV cell may only be a few centimetres in size. A PV solar panel will consist of hundreds of PV cells. This allows solar panels to be scaled up in size while keeping the panels efficient. It also means PV solar panels can be built to almost any size, depending on need.

The two semi-conductor layers and the metal conducting plates are placed within glass or plastic to protect them from the weather. As both glass and silicon typically reflect some light, which would reduce how much light is absorbed, an anti-reflection surface is also added. Finally, the panel will have some kind of backplate which can modulate the temperature of the panel. This is because one of the major limitations to PV systems is, surprisingly, heat.

Limitations of Heat

It doesn’t seem very intuitive to suggest that high temperatures and solar power don’t go well together, but it’s true. Modern state-of-the-art solar panels will generate about 10-15% less power during heatwaves, depending on their construction and the temperature.

The reason for this is because heat provides a different kind of energy to the solar panel than light. Instead of the electrons being knocked out of the atom, heat gives them more energy to move about within the atom. The electrons move faster because they have more energy. This means that the photons from the light are less likely to hit an electron and knock it out of the atom. If the photons aren’t knocking electrons out of the atoms, then there are no free electrons to create an electrical current within the solar panel.

What it is important to understand though is that, until you get to extremely high heats (upwards of 80°C), heat doesn’t damage the solar panel at all. It will just generate less power per hour, the same as if there was heavy cloud or a storm. Given most heatwaves occur during the summer, when there are much longer daylight hours anyway, this lower generation may be compensated for.

It is also the case that scientists and engineers working on solar panels are fully aware of this limitation and are working hard to mitigate these limitations. Building temperature regulation into panels is a big one. Some types of solar panels, too, are naturally more resistant to heat although better heat resistance comes with a trade-off with cost.

What about other limitations then?

Cost and Efficiency

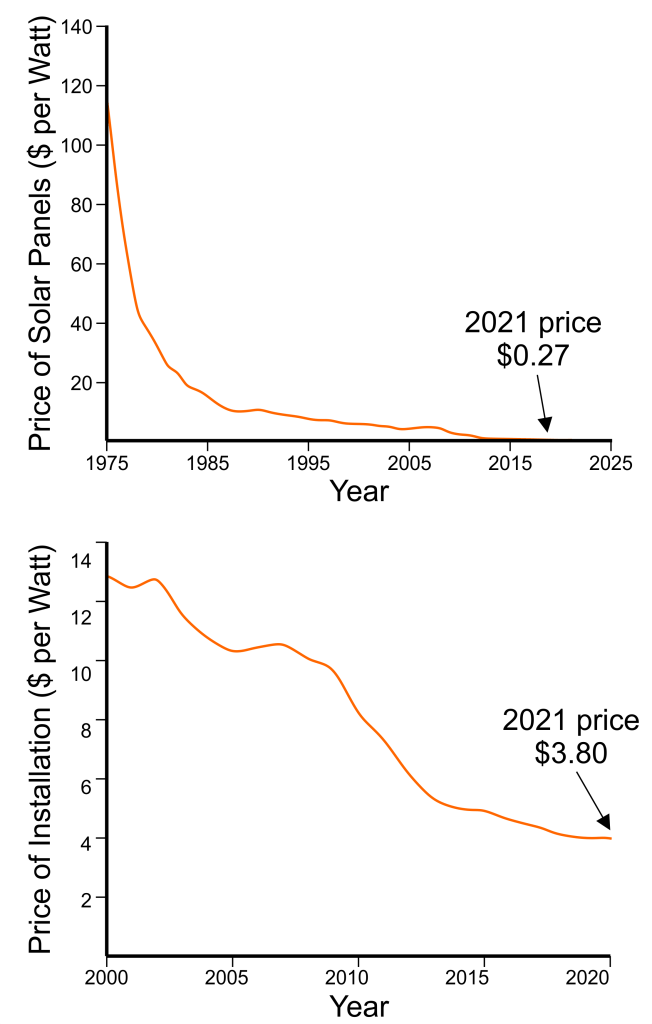

PV solar panels aren’t cheap. Although there’s a low maintenance cost, because there are no moving parts, there’s a significant initial investment. Prices have dropped a lot over the last decade, both for the panels themselves and for installation, but typical prices are in the region of £5-7,000 in the UK or $12-16,000 in the US for a 5kW system without a battery (enough to power a four-bedroomed home). Of course, this price can be offset by savings on your energy bills and joining a scheme to sell any excess power you generate to the local or national grid. How soon those savings will offset the initial price varies a lot depending on your electricity usage and how many panels you have.

Then there is efficiency. This is somewhat misunderstood by many because it is viewed the same way as efficiency from traditional power sources, like oil and gas. Oil and gas cost money. In order to generate enough electricity to offset their cost you need to have a very efficient system. Any energy in the oil and gas that is not converted to electricity is wasted money.

Sunlight, however, is basically free. Once the solar panels are installed there are no additional costs and the panels will run for, on average, about 25 years with minimal costs beyond occasional cleaning. Thus, any sunlight that is not converted into energy can’t really be considered wasted. You don’t lose money by having a low-efficiency system, it will just take longer to offset the initial costs.

The maximum efficiency any PV solar panel can reach is about 35%, but most solar panels used domestically are in the region of 20-25%. This means the solar panel can convert about 20-25% of the energy in light into electricity. For comparison, plants are thought to have a solar efficiency of about 0.1-0.2% for photosynthesis.

Are solar panels worth it?

Knowing the science behind solar power is one thing, but the question remains whether solar panels are worth the high initial investment.

In short – it depends.

In an ideal world, the answer is yes. Solar power is an excellent form of renewable energy, reducing our reliance on high-emission forms of power such as oil and gas. It’s also a great way to lower energy demand on the national grid, which will help avoid issues with power generation as we transition from fossil fuel-based systems to renewables. There are innumerable benefits to domestic solar panels and they are becoming more and more popular for a reason.

However, there is no getting around the initial upfront costs. Prices have come down and continue to come down for the panels themselves, but the actual installation costs will always be dependant on labour and admin fees. If you can’t afford solar panels, you can’t afford them. If you can afford them, but are planning on moving house before their initial installation price is offset, then it might not be worth the investment.

Not every house is ideal for solar panels either; the orientation, slope and strength of the roof matters. If you live in a flat-roofed apartment building, then the question of solar panels is academic. On shared flat roofs, solar panels simply aren’t cost effective with the current technology.

That doesn’t mean solar panels should be dismissed either. A low-emission society does not have a one-size-fits-all policy, the way a high emission society does. The more houses that have solar panels, the better for everyone else. Both because there is less demand on the grid overall and because those houses can and will sell electricity back to the grid which means more electricity from solar is available.

In short: solar panels are definitely a good investment for some people and should be considered by any homeowner conscious of their carbon footprint. However, not everyone can make that investment and that’s okay too. There are other ways to reduce your emissions that don’t have the big upfront costs.

Leave a comment