Scientists don’t agree on the causes of climate change, certain parts of the internet will insist. How can we truly be expected to change our very way of life, if the science isn’t even certain at this stage?

That’s a fair comment and an understandable one. You don’t have to look far to see situations where the science wasn’t conclusive, but people assumed it was and acted on incomplete information causing untold harm and disaster. The Thalidomide scandal is the typical example used, for what can happen when the science hasn’t been rigorous enough.

Yet, is the statement that ‘scientists don’t agree on the causes of climate change’ actually true?

Firstly, we have to understand that there is a distinction between a scientist’s opinions as an individual and the scientific evidence that is published by scientists. We should also remember to make a distinction between a ‘scientist’ and a ‘climate scientist’. There are a lot of scientists in the world but most of them aren’t specialised in climate or earth science.

How do we know, then, if scientists really do agree or not? Well, ideally, we need to look at the scientific research climate scientists are publishing.

How does scientific research get published?

Most research is published in the form of articles in a scientific journal. A scientist or group of scientists will write an article detailing their most recent research and the conclusions they came to. This article will vary in length, depending on where they hope to get it published, but will typically be somewhere between 3000-12,000 words. Once the scientist or group of scientists is happy with the article, they will then submit it to a journal of their choice. At that point, they have to sit and wait for the journal to either accept or reject the article.

The decision on which articles to be published lies with the editing team – the Chief Editor or Editor-in-Chief for the journal and then, depending on the size of the journal and the topics it covers, there will also be editors in charge of different topics. These editors will have a science background, usually in the field the journal covers, and have probably been published themselves at some point.

As an example, one of the biggest and most famous journals for geoscience in general and climate science in particular is Nature. Nature has the reputation that it only publishes the best and most innovative research. Examples of important papers published in Nature include: James Watson & Francis Crick’s paper on the structure of DNA; Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner & Jonathon Shanklin’s paper identifying the hole in the ozone layer; and Georges Köhler & César Milstein’s paper on manufacturing specific antibodies that allowed treatment of autoimmune disease and cancer.

Nature’s current Editor-in-Chief, who has the final decision on what articles are published is Magdalena Skipper. She has a background in genetics including a PhD from the University of Cambridge and had a number of papers published on sex determination before she joined the editorial team at Nature.

However, Nature as a journal covers more than just genetics. It also covers medicine and biology, zoology and environmental science, geoscience, climate science, planetary science, engineering and so much more. More than any one person could hope to be an expert in. So, Magdalena has a team of editors who specialise in other topics and they will advise her on what articles are best for the journal.

There are two issues with this format however. Firstly, in a big journal like Nature, the editors receive hundreds of articles a day. They do not have the time to thoroughly check every single article to make sure that the conclusions in the article are backed up by the science presented. That is a time-consuming process, it can take hours for even one article, especially if there is some new or innovative method being used, or the conclusions of the article contradict the established norm. The editors therefore need help to get through the sheer volume of submissions.

The second issue is that science is incredibly specialised. A topic covering climate science can include a vast array of different research projects including: the mechanics behind how our climate works, different ways of modelling the climate to produce climate projections, measurements and analysis of past climate and analysis of the impacts climate change will have. Each of these projects will have even more specialisation.

As a further example, my own research has been on the history of glaciated landscapes and I use a process called seismic reflection to look at rocks preserved under the sea floor. This is included in ‘analysis of past climate’. However, another scientist may use drill core samples to investigate how global temperatures have changed over time. This is also ‘analysis of past climate’ but uses very different techniques. If submitting to a journal like Nature, which has such a broad reach in terms of the science it covers, articles from both myself and the other scientist would probably go to the same editor. In the case of Nature, either John VanDecar or Juliane Mössinger who are the senior editors for Earth Science at Nature.

This means editors can be faced with an article where they are familiar with the basic premise, but cannot be considered an expert. In this situation they may not feel fully qualified to assess the science and ensure it meets the rigorous standards the journal expects. If Nature started to publish articles that had errors or conclusions that were not backed up by the science, they would lose reputation and money.

The solution to these two issues, time and expertise, is to simply get outside help. This is where peer-review comes in.

What is Peer Review?

Peer review is basically what the name implies. The article is given to peers – other scientists working in the same field – to review and to decide if the science is good enough for publication.

Generally, the article will be given to a minimum of two or usually three reviewers. The reviewers will then go through the article, line-by-line and find any mistakes or sections where the science is not fully explained. This may just be an issue with the structure and grammar of the article, or it may be an issue with the method used to analyse the data.

By the end of the review, they will have usually a couple of pages of notes on any errors and at that point they write a message to the editor either advising to accept the article with no changes, to accept with minor changes, to reject with the opportunity to re-submit after major changes or to outright reject with no re-submission. It is incredibly rare for any article to be accepted with no changes.

The editor receives the reviews, again at least two of them, and then makes a decision on the article based on the advice of the reviewers. Occasionally, the editor will look at the article themselves and overrule the reviewers, but this is also rare. The decision and the reviews themselves are sent to the lead author of the article. There is no appeal process, the decision you receive is the final decision.

At this point the scientist or group of scientists can choose to make the changes requested by the reviewers and send in a revised article, or they can submit it to another journal. The latter only really happens if the article is rejected entirely and will usually come with some changes to the article based on the reviewers’ response anyway. The important thing to note is that you do not have to make all of the changes the reviewer demanded, as long as you can successfully explain why that change was not made.

If the article is accepted with minor changes, there is usually a time limit on making those changes – typically 30 days or so. This is because the changes should be minor enough to make the corrections quickly. Major changes are rejected with an invitation to resubmit mainly because it will typically take longer than 30 days to make the changes the reviewers asked for. The time limit is generally to help the journals properly schedule publication; peer review is a slow process already so they need to encourage a quicker turn around.

Once the revised article is sent back to the journal one of two things can happen. The editor may look at the corrections that have been made and accept that they have covered the requirements of the reviewer and approve the article for publication. Alternatively, the editor may look at the corrections and decide it needs to be sent for a second review. This can be with the same reviewers as before, but may be with new ones, it depends on the editor and the article.

Eventually, after any number of reviews, the article is either accepted for publication or, if the writers of the article refuse to make any corrections and fail to defend that decision, it is thrown out entirely.

Peer review, therefore, is designed to have the experts in the field maintain the standards for the field of science involved. An article which has gone through peer-review has been shown to have proven itself to those who understand every aspect of the science involved. You can’t just publish whatever you want, with bad data and wild theories and say your science is correct and everyone else is wrong. If you can’t back up your conclusions, you’re going to be thrown out by peer review.

The Limitations of Peer Review

This is how peer review works in theory, but does this carry across into practise? Well, the answer is complicated, as many things are.

As science gets very specialised, it’s often the case that scientists will personally know the person who is peer reviewing their work and may have worked with them before. There’s a perception, therefore, that those reviewers will be less demanding with their review to get a colleague’s article published. This is definitely something that has happened in the past and probably still happens in some situations, especially as it’s nearly impossible to really do a double-blind review i.e. the reviewers do not know the author of the article. Chances are, the reviewer already knows the project from academic conferences and general conversations and networking with their colleagues and can work out the author even if it is not given.

However, the vast majority of scientists today are well aware that, just like the journals, the science research that they do for a living relies entirely on the peer review process being both thorough and transparent. Any doubt on the validity of the peer review could destroy the livelihoods of millions of scientists across the globe.

Obviously, the experience any scientist has with peer review is going to vary incredibly, depending on their specialisation and which journals they are trying to publish in. My experience with peer review has been that even those scientists who thoroughly agreed with my conclusions were very thorough in making sure that my evidence backed it up. Even if that meant demanding a major re-write. If anything, I found the peer review process to be very harsh with very high expectations, which is as it should be. Other people, of course, my have different perceptions on it.

This is also where the reputation of the journal comes into play. Scientists will generally try and publish their articles in the most reputable journals possible, because of the high standards for both articles and peer review. Nature, for example, will likely never find it difficult to get experts in the field to agree to review articles for them and the peer review process is going to give better results. A smaller journal with a poorer reputation or a reputation for not having a thorough review process is going to struggle to get expert reviewers.

What is sometimes implied by those trying to cast doubt on science publication is that scientists have a financial incentive to push through certain articles without a proper peer review process. This is actually not the case, for one major reason: peer review is an entirely voluntary process.

By this I mean that no scientist, anywhere, is getting paid to conduct peer review. It is just considered part of the job. Scientists don’t even get paid for the articles they have published. In fact, there are plenty of journals that will charge the scientists themselves for publishing in their journals. Most journals have an extra charge to include colour images in the article, some will have processing fees and every journal will charge the scientist if the scientist wants to publish the article ‘open access’. This means that anyone can read the article without having to buy a subscription to the journal itself.

This means that, strictly speaking, publishing science and involving the peer review process actually costs scientists financially. They put in hundreds of hours of completely unpaid work so that there is a degree of credibility to their research that they wouldn’t get from publishing elsewhere. If you read a scientific article in Nature, you know that it has reached an extremely high standard of review.

Given that most scientists are paid based on the research grant money they bring in and those grants are given out on the understanding that there will be articles published, the peer review process is making their lives harder. Yet, while peer review is long, harsh and expensive for scientists, it persists because it infers a certain standard has been met and that the results are reliable.

Peer-Reviewed Climate Science

What does this mean, then, when it comes to climate science?

The oft-quoted statistic for climate science is that 99% of climate scientists have the opinion that the causes of modern-day global warming and the associated climate change. This isn’t quite accurate, however.

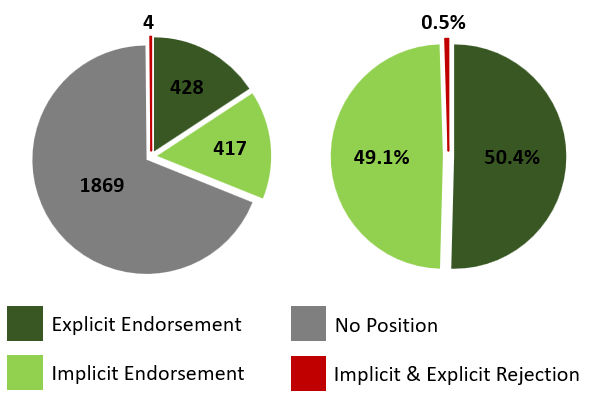

The actual statistic is based on the analysis of thousands of peer-reviewed scientific articles on climate. 99% of those articles agreed the root cause of modern-day global warming was human activity (Lynas et al 2021). It is not, as is suggested when this statistic is quoted, merely a matter of opinion. It is a situation where thousands of studies into the causes of climate change have found no evidence, at all, to suggest that humans are not the root cause of this period of unprecedented global warming.

These are studies backed by incredibly detailed scientific research and, usually, torn apart several times during the peer review process to make absolutely certain that the conclusions made are backed by the evidence.

There is still some debate, that much is true. The exact details of how certain parts of our climate will respond, or how many emissions we can release before irreversible damage can be done are still being researched today. Articles are going into peer review every day and are critiqued by colleagues. However, the fact that some details are still being debated tells us something about just how thorough that consensus is.

The whole peer review process works because even if you agree with your colleague, you are going to pick apart their methods and analysis during review. Both of your livelihoods rely on it. Scientists have to argue about stuff, because if they don’t, the peer review process suddenly stops working.

So, for any analysis to find that 99% of peer reviewed articles agree, without qualification, that humans have caused climate change, is a huge deal. This kind of consensus doesn’t really happen that often.

Do Scientists Agree Then?

In short: yes.

Overwhelmingly climate scientists across the globe have found no conclusive evidence that modern day global warming and the climate change associated with it were caused by anything other than humans.

Some of the exact details, scientists are still arguing about. The climate is a very complicated thing and our records only go back so far, which is a problem when some of the mechanisms involved take hundreds or thousands of years to react. However, in the last 50 years that climate scientists have been studying this situation the certainty has only increased. Scientists are more certain than ever that global warming and climate change are going to have a negative effect on the world and on society.

The idea that scientists don’t agree is, quite simply, misdirection and nothing else. It’s an attempt to undermine the reality of the situation. Don’t fall for it.

Leave a comment