Global warming is causing climate change, scientists have told us. We know that greenhouse emissions are causing global surface temperatures to rise. We also know that the climate changes alongside global temperatures and has since the formation of the Earth. It isn’t a surprise, then, that the global warming is changing the climate.

How is the climate changing, though? We know places are getting warmer, but apparently, they are also getting wetter and we’re getting more extreme weather events. Why? What does temperature have to do with rain and storms?

Surprisingly, the answer is ‘a great deal’. It turns out that global surface temperature is the biggest single thing controlling our climate and weather. This is because surface temperature directly controls the temperature of the air. Air has quite a few interesting properties that depend entirely on temperature.

Temperature causes air to move

When sunlight hits either the land or the ocean, most of the light is reflected, but some is absorbed and is transformed into heat. This warms up the land and the ocean. As heat will always try to move from hot areas to cold areas, the cooler air that touches the land and ocean also starts to warm up.

Warm air is less dense than cold air. The warm air has more energy and the molecules that make up the air will move further apart. As the molecules are further apart, they are less dense and so will rise above any cold air. This is why heat rises.

As the warm air rises high into the atmosphere, the insulating effects of our atmosphere are weaker and much of the heat from the air is then lost into the freezing cold of space. This creates a temperature gradient from warm air close to the surface to cold air high up in the atmosphere.

Back at the surface, as the warm air rises it has to be replaced by something. Cold air, which is denser, is already trying to sink below the warm air, so it is this that is dragged down from higher up in the atmosphere to replace the warm air. In this way a cycle is formed of air starting to warm, then rising, cooling down and sinking again. Meteorologists call this a cell. These cells can form on a variety of scales, but the very largest ones determine the climate from the tropics to the polar regions.

This brings us to the next property of air – pressure.

Temperature affects air pressure

Air cells affect air pressure, sometimes called barometric pressure, because the surface of the planet is not heated equally all over. The ocean, for example, will absorb a lot of heat from sunlight but heats up much more slowly than the land. This means the air above water is heated less than the air above land. Similarly, the regions around the equator receive a lot more sunlight and heat than the areas towards the North and South Poles.

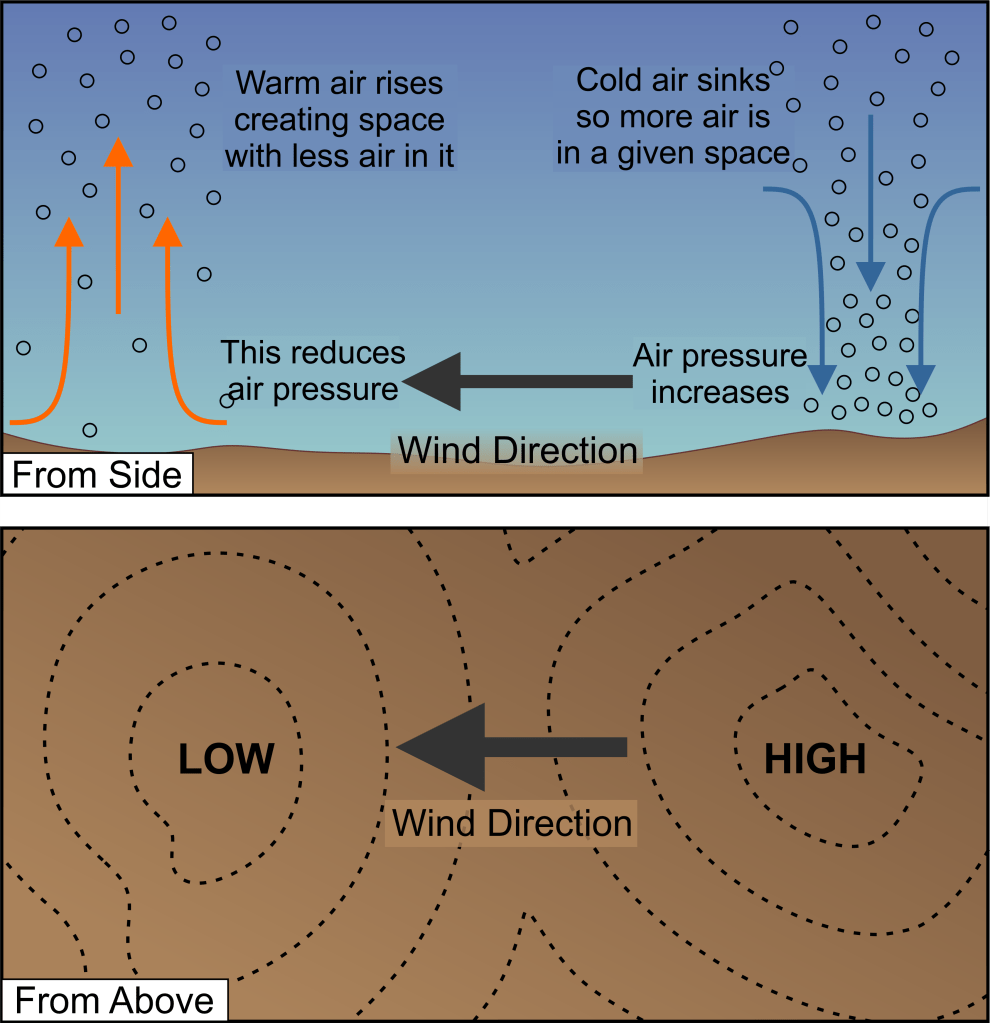

Where air is being heated and the warm, less dense, air starts to rise the air pressure reduces as air molecules are moving away from the area and spreading out. The warmer the air gets, the less the pressure. Where cold air is being drawn down to the surface to replace the warm air, it is getting denser. More air is being pushed into a smaller area and so air pressure increases. Colder regions, with denser air, will generally have greater air pressure.

In physics and nature in general, everything tries to be as equal as it can be. Heat transfers to cold areas because it is trying to equalise to the same temperature. The hot area has more energy and so gives some to the cold areas. The same is true of pressure. Areas of high pressure will try to push that excess pressure onto areas of low pressure, in order for both areas to end up with equal pressure.

Air tries to travel from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. This movement is the wind. The bigger the difference in air pressure, the stronger the wind. As air pressure is determined by air temperature, then bigger differences in temperature create bigger differences in pressure, resulting in stronger winds.

This brings us then to the final property of air – water vapour.

The water cycle is driven by heat

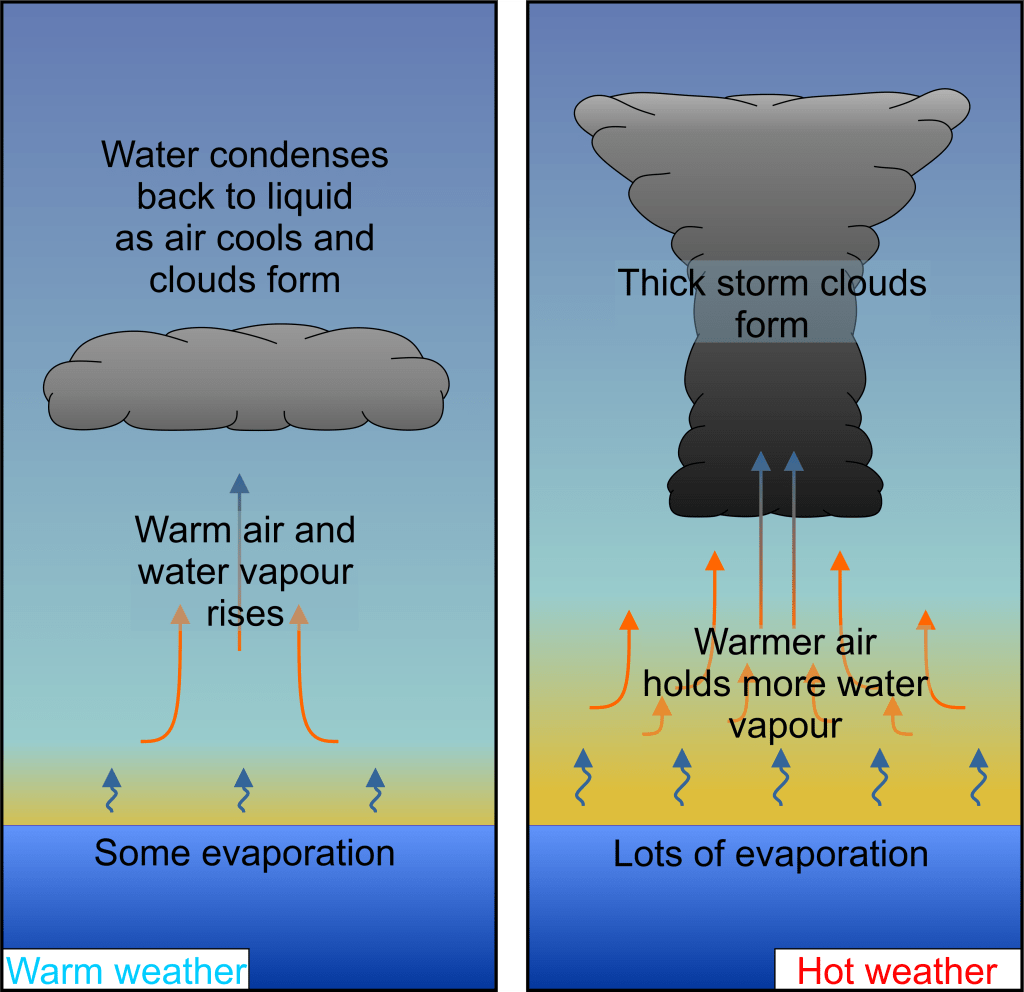

Our atmosphere is made up of a certain amount of water in a gas form i.e., water vapour. The amount of water in the air at any given time is controlled mainly by temperature. Warm air, because it is less dense, can carry much more water vapour than cold air. It has more space for the water molecules to exist.

When the surface warms under sunlight, not only does the air around it become warmer but also any water on the surface starts to evaporate. The water vapour that forms is mixed into the warm air. As the warm air begins to rise, the water vapour goes with it. However, as the warm air rises it also starts to cool. It can now hold less water vapour. The water also cools and tries to turn back into liquid water. The water will condense around tiny particles of dust in the atmosphere and collect into clouds.

As the clouds form, they are heavier than the air around them and will begin to sink. If there is enough water vapour being evaporated, lifted, then cooled and condensed into clouds it will eventually become so heavy it will start to rain. The water is transferred back to the surface and the cycle begins again. This is the Water Cycle.

The evaporation of water, the formation of clouds and rainfall itself are all controlled by temperature. Mainly, how warm the air gets. The warmer the air, the more evaporation and the greater amount of water vapour it can carry high into the atmosphere. Clouds form where the air begins to cool and the water vapour condenses into water droplets.

From the last section, we know that warm air has lower pressure. We can now see that clouds form in those areas of low pressure. If the area of low pressure moves then the clouds will move with it.

Monsoon season is the result of temperature change

Air cells and cloud formation are all well and good, theoretically, but to understand what this means for climate change we need to look at real examples. As it so happens, one of the best examples of temperature control on weather and climate is the tropical climate and the tropical monsoon.

The tropics are generally defined as the region either side of the equator. The region is bounded in the north by the Tropic of Cancer and in the south by the Tropic of Capricorn, each found at 23 degrees latitude. This is the area of the earth that receives the most sunlight over the course of the year. The temperatures around the tropics don’t vary much over the course of the year. However, although they don’t see the same ‘summer’ and ‘winter’ pattern that higher latitudes do, they do have a strong seasonality. The dry season and the rainy season – often called the tropical monsoon.

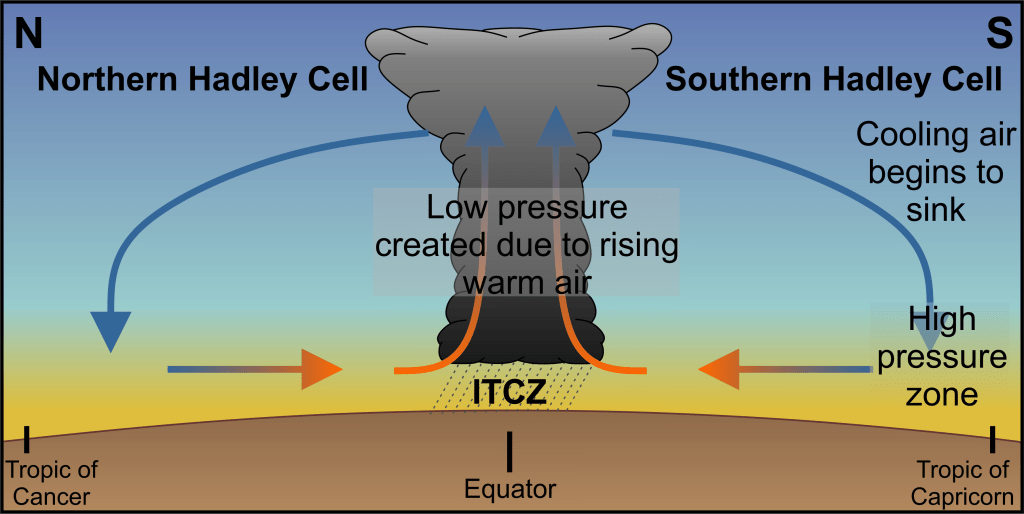

The heat at the equator, results in very warm air which rises quickly into the atmosphere creating a low-pressure zone around the equator. This heating occurs all year round and so the low-pressure zone is maintained all year round. The rising warm air will move north and south on each side of the equator, into cooler regions. The air then cools and sinks creating areas of high pressure in these zones. Due to the pressure difference the winds blow back towards the equator. This air cell is called the Hadley cell and the area of low pressure is called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) – because the powerful winds blowing from the tropics converge here.

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is responsible for towering clouds, several kilometres in height, because so much water is evaporated at the surface and carried high into the atmosphere. These clouds are what causes the rainy season or monsoon. However, the convergence zone is not stationary, it doesn’t always sit on the equator exactly. Instead, over the course of the year, it will shift north and south and take the rains with it.

This is because while the tropics receive similar amounts of sunlight all year around, the areas further north and south don’t.

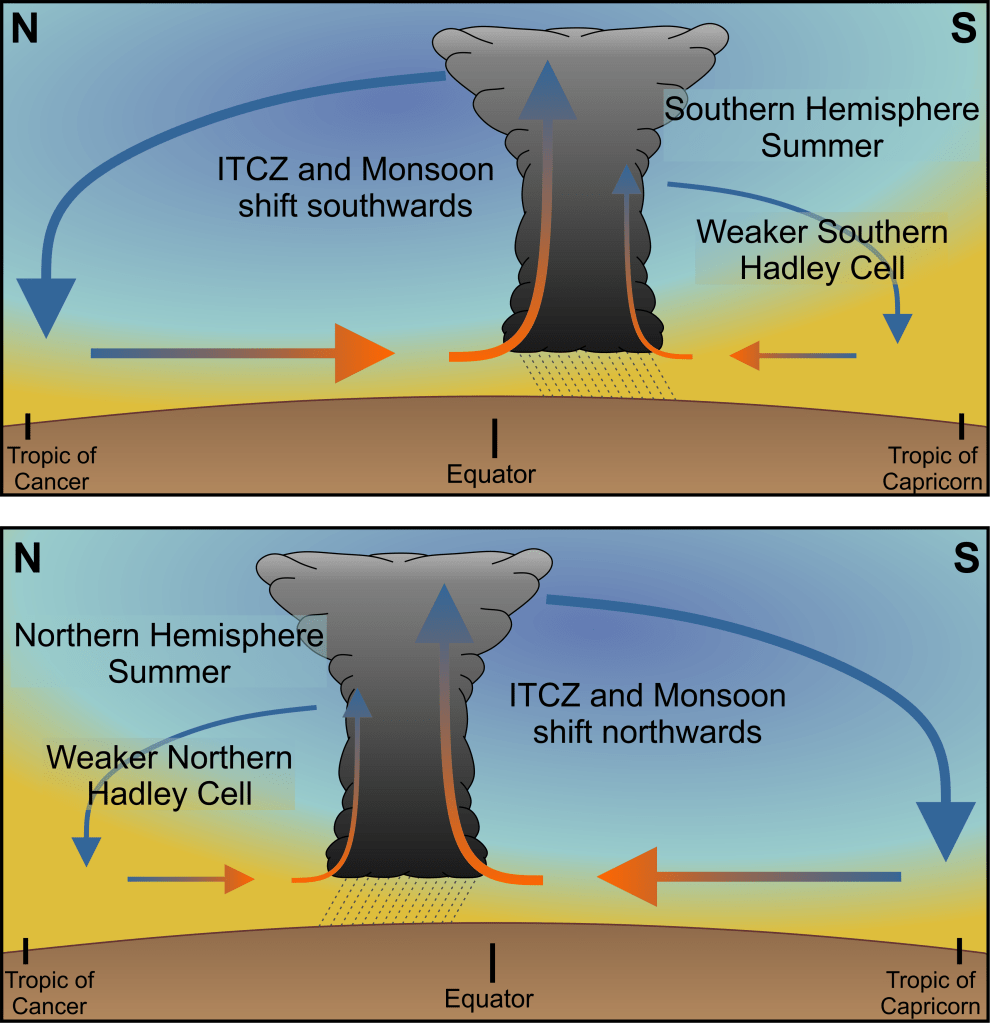

During the northern hemisphere summer, the area north of the equator receives more light from the sun and a lot more warmth. The temperature between the Tropic of Cancer and the equator is now very similar. The temperature difference decreases. As we discussed the temperature difference determines the pressure difference and thus the strength of the wind. In the northern hemisphere summer, the weak temperature difference means the northern side of the Hadley cell is weaker.

At the same time, the southern hemisphere is in the winter and is receiving less light and less warmth. The south is cooler. This means the temperature difference between the Tropic of Capricorn and the equator increases. As the temperature difference increases, the pressure difference increases and the winds get stronger. The southern Hadley Cell is stronger.

As the southern Hadley cell is strong and northern Hadley Cell is weak, the ITCZ is pushed towards the north.

The reverse happens during the southern hemisphere summer. The temperature difference between the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn reduces so the southern Hadley Cell weakens. The temperature difference between the Tropic of Cancer and the equator increases, so the northern Hadley Cell strengthens. The ITCZ is pushed southwards.

The convergence zone is also affected by whether it is over land or ocean.

The ocean warms much more slowly over the course of the year and is generally cooler than land. This means that at the equator the air is cooler over the ocean and hotter over land, regardless of the time of year. This means the temperature difference between the equator and the tropics will always be less over the ocean than over the land.

A weaker temperature difference means weaker winds and a weaker Hadley Cell. Thus, the ITCZ will not swing as far north or south over the ocean as it does over land.

Countries in the tropical zone will often go months without any rain at all, only to receive constant rainfall for days at a time once the ITCZ arrives. The few places that do have regular rainfall tend to be tropical rainforests where the forests themselves trap much of the moisture and create very strong but also very localised and short-lived air cells.

Climate change will strengthen the tropical monsoon

The strength of the ITCZ is dependent on the temperature at the equator. The movement of the ITCZ depends on how different the temperature at the equator is from the temperature at the poles. Therefore, we can expect that the tropical monsoon will be strongly affected by global warming. This is the case.

As previously stated, warmer surface temperatures, generally, means more rain. The tropical monsoon already brings with it amounts of rain that can be devastating simply because of how much falls in such a short space of time. Flash floods are already common in southern Asia and across Africa during the monsoon and they will get worse as the tropical monsoon becomes more intense. Scientists have used scientific drilling in India to examine how the monsoon changes with climate and found a very clear link between the climate, CO2 and the strength of the monsoon (Clemens et al, 2021).

However, there is the added issue that global temperatures are not rising at a consistent rate. Scientists have seen that the poles are warming more quickly than the equator. So, too, is the land warming much faster than the ocean. Although the evidence is not yet overwhelming, recent reviews of the science strongly supports the idea that, under future warming, the ITCZ will become both narrower and more focused on the equator i.e. covering a smaller area and moving less (Bryne et al, 2018).

That could lead to many areas in the tropics, that are already typically dry, seeing far more droughts as the monsoon fails, while areas around the equator will bear a larger brunt of the increased rain.

When the International Panel for Climate Change warns of increased rainfall and increased number and intensity of storms, the ITCZ represents a good example of what they mean. Warmer weather means more evaporation and stronger areas of low pressure. More evaporation and more intense low pressure mean more severe storms.

Another example is hurricanes. Hurricanes are formed over ‘hotspots’ of ocean temperature, where very warm patches of ocean create small areas of intense low pressure, which develop into storms. Stronger hurricanes form when those storms travel over warm ocean sucking up more heat and moisture and deepening the low-pressure system. Under global warming, more of the ocean will meet the needed temperatures to form those low-pressure regions that eventually become hurricanes.

The connection between global warming and the increased number of and intensity of storms isn’t an obvious link, from the outside. However, we also don’t have to look far to find straightforward examples either. The tropical monsoon is already one of the most intense storm systems the world sees, with near constant, heavy rainfall. This system is almost completely controlled by temperature, both in its formation and in its movement across the tropical regions.

Any change in global temperatures, therefore, will strongly impact those storms and could change the lives of millions of people who rely on them.

Leave a comment