On long journeys have you ever looked out of the window at the hills and fields around you and seen something strange about the landscape that you didn’t understand? Perhaps it’s a steep-sided hill in an otherwise flat area. Maybe it’s a strangely shaped valley with a river that looks too small to have carved it? It could be long grooves in the landscape that seem to uniform to be formed naturally but too big to have been put there by humans for no real reason.

Although you might not have known why the landscape looked the way it did, by noticing and thinking about it you have taken part in one of the oldest forms of earth science. The study of the landscape, how it was formed and what this means for the history of our world.

In the modern-day scientists have a lot of tools they can use to understand the Earth and its climate. We’ve talked about one previously, scientific drilling, when discussing the role of carbon dioxide. Today we are looking at another; landscape evolution.

What is landscape evolution?

Landscape evolution is how the landscape around us changes over time. This is something that happens constantly, but also slowly. Rivers change course, cliffs fall into the sea, mountains wear down into hills. If we know what causes the landscape to change and how, then we can look at a landscape in the present and work out what has occurred in the past.

There are a lot of different process that occur to shape the landscape, and they all interact with each other. However, they generally fall into three major categories: human activity, tectonic activity and the combined action of erosion and deposition.

Human activity is a relatively recent process, at least when talking about the landscape, but also a very fast one. Natural processes take thousands or even millions of years to shape the land. Humans, on the other hand, can mine out new canyons in a few decades. They build their own rivers and lakes in the form of canals and reservoirs. Cities are the equivalent of animal burrows and nests, but on a scale that completely changes the landscape.

Tectonic activity is the slowest process that affects the landscape. However, it can have just as drastic an effect on the landscape as human activity. The movement of tectonic plates creates and destroys entire continents, as well as mountain ranges and deep canyons. Volcanic eruptions in the ocean often create islands, while earthquakes have been known to divert rivers or cause tsunamis which flood vast areas of land.

Finally, we are left with erosion and deposition. These are two sides of the same coin. Erosion is the process by which land is worn away, transporting sand and gravel and rocks away from where they once were. Deposition is the process of putting these materials down in a place where they were not created. A river wears away at its banks and the sand and mud are transported downstream where they reach the sea. At the sea, the sand and mud are laid down and shaped by the waves, creating a beach. Erosion and deposition are strongly affected by climate, directly or indirectly. Wind and water are the two biggest causes of erosion and both are dependent on climate. Dry, hot environments see a lot of wind erosion and can form sand dunes. A cold, wet environment has lots of rainfall and rivers, but may also have glaciers and ice sheets that literally carve their way through the existing landscape.

Using the landscape as a tool

The strong link between climate and erosion and deposition actually makes landscape evolution a powerful tool for climate scientists. Modern day climate change is influencing processes that usually take decades or even centuries to occur. Scientists can’t rely solely on modern climate data – there simply isn’t enough of it. However, these processes have been occurring for the whole history of the planet and there is plenty of evidence of them to be seen in the landscape.

As an example, we can look at how a landscape changes due to the action of ice and what is left behind when the ice disappears.

Ice can start to collect anywhere that receives enough snowfall and doesn’t get warm enough for the snow to melt away. This happens most often in mountains as the high altitude means they are consistently cold throughout the year and clouds tend to drop snow rather than rain. The snow collects in hollows in the mountainside and will eventually become ice. As more ice forms, the weight of it starts to drag the ice downhill. Once the mass of ice becomes large enough it starts to flow, usually in the form of a glacier.

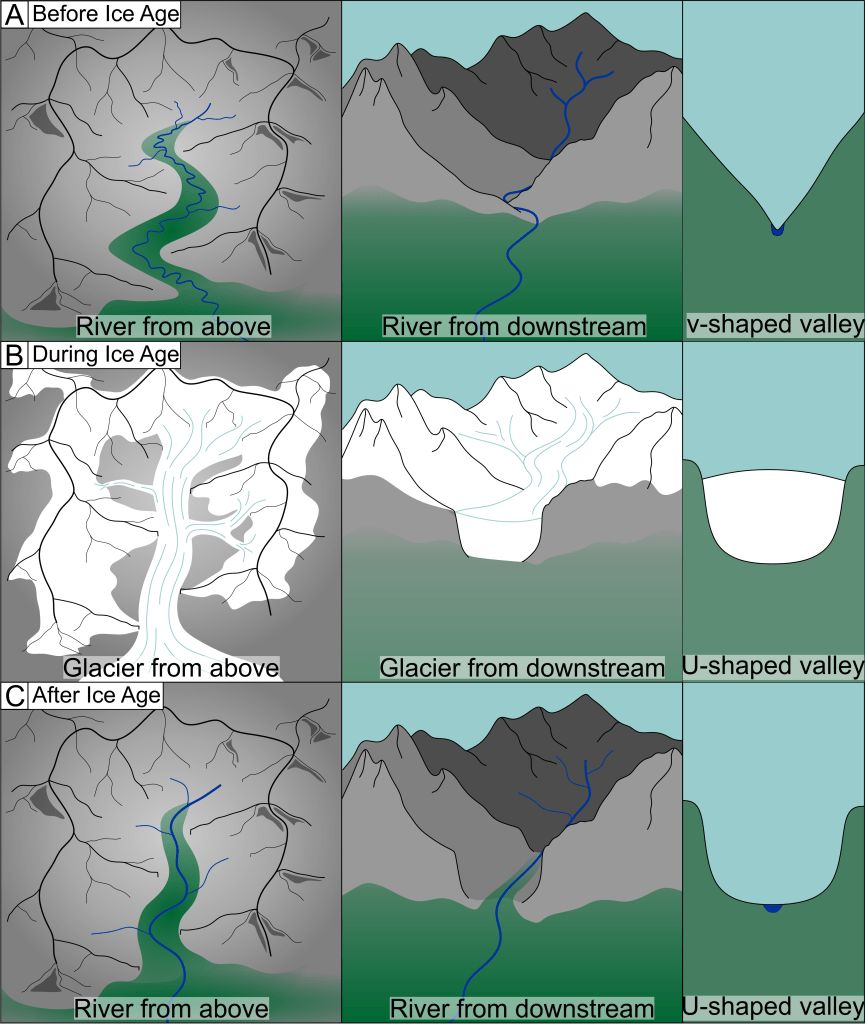

When water flows downhill it will always take the easiest possible route. Ice works the same way. When the ice starts to flow downhill it tries to find the easiest path. This is almost always river valleys, because the water has already found the easiest path and the ice can just follow it. However, the glacier is going to be many times larger than any rivers. It can erode far more than a river can, and it won’t fully fit in the narrow river valleys. Instead of finding a different path, the glacier simply carves into the valley until it is big enough.

In the mountains, river valleys tend to have a very characteristic ‘v’ shape that wiggles back and forth in between the slopes of different peaks as the river seeks the easiest path. The rivers in mountains are quite small and it’s easier to work between these slopes than try to cut through them.

The glacier, however, will bulldoze its way through those slopes as it widens the valley so it can fit. Valleys carved by glaciers form a very clear ‘U’ shape with a flat bottom and extremely steep sides. They also tend to be straighter than river valleys, though they can still curve around some of the bigger obstacles.

After the ice leaves, the river is left behind. This river is no bigger than the one that was there before the ice was formed and so it tends to be far too small for the size of the valley. This means it is unlikely to significantly erode the landscape after the ice leaves and so the landscape remains dominated by the ice even long after the ice has disappeared entirely.

Eventually, the sides of a ‘U’ shape valley will be worn down, but this will be mostly through the action of rain destabilising the extremely steep slopes causing landslips. However, even if the slopes of the valley lose their characteristic ‘U’ shape, the river will always be smaller than the valley and so it is easy to tell that the valley was once inhabited by ice.

Landscapes can inform climate science

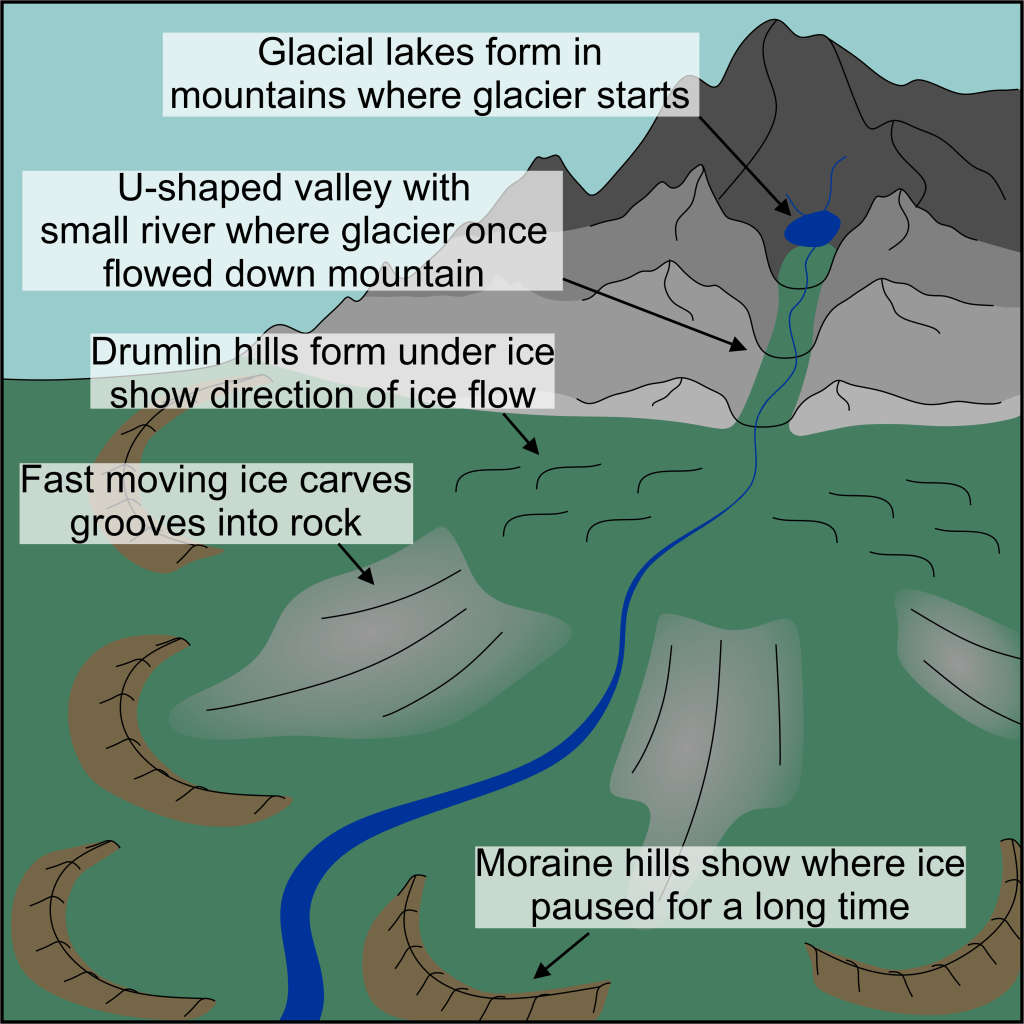

This is just one way in which ice can interact with the landscape. There are many other features in the landscape that can be created by the action of ice. Many of these features persist long after the ice has disappeared. Scientists use these features in order to map out where the ice has been, what direction it was flowing and even how fast it was flowing. The landscape can also tell us when the ice disappeared from the landscape and how fast it disappeared, even thousands of years after the ice has melted away.

In modern day climate change, the loss of ice is a huge problem and scientists have been warning us about the consequences for a while. The melting of the huge ice sheets will cause sea level to rise significantly, threatening coastal communities. Mountain communities aren’t safe either, as melting glaciers have a tendency to cause periodic flooding. Then, once the glacier has disappeared entirely, those communities will be left with much less available water.

These consequences appear to be obvious. However, they are only obvious because the evidence for them has been seen in the landscape over and over again. These are all things that happened around 19,000 to 12,000 years ago when the Earth came out of the last ice age. We can see where the coastline used to be, before sea levels rose. We can see where huge floods caused by melting ice sheets flowed. We can see the tiny rivers that now occupy valleys that are far too large for them and know when the glacier vanishes only a small river will remain.

Scientists have looked at the landscape, understood what it was telling us about the past climate and then set about to use that information for our current situation.

Technology has advanced the study of landscapes

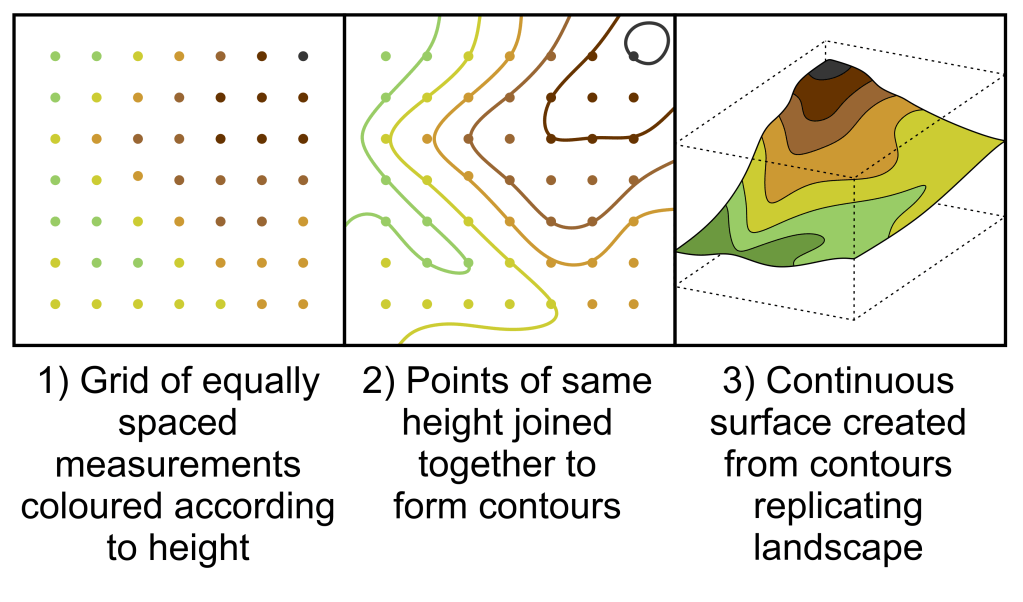

In the past studying the landscape meant going out into world and drawing the landscape, creating hand-drawn maps with careful measurements taken. These studies could take years for a relatively small area, because creating the maps took so long. In the modern day we can use a combination of satellite data and photographs to create highly detailed 3D images of the world around us. A digital elevation model, or DEM, is constructed from taking measurements of height on a regular grid. The measurements are fed into an algorithm which predicts how high the land is between two points in the grid to turn it from a grid of individual points into a continuous surface.

For looking at large areas of land, the measurements typically come from satellite data and you can expect the grid spacing to be around 1 km. Occasionally, very high resolution DEMs will go down to 50 or 100 m. This means small details are often lost, because the way the grid is used to create a surface does cause some smoothing of the landscape. However, in large scale studies the fine details are not what you are looking at, but rather the large-scale features, such as the previously described ‘U’-shaped valleys.

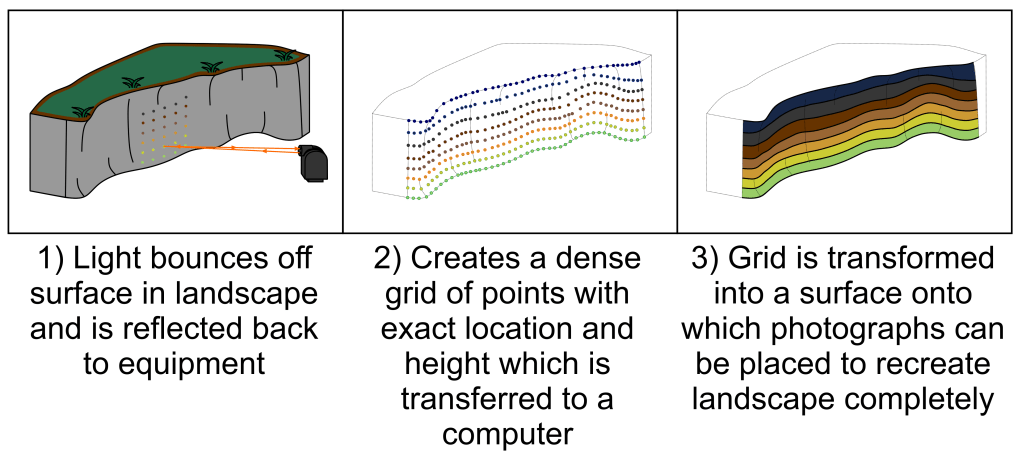

To look at the fine details you are likely to be studying a single feature within a landscape. For this a scientist will probably use a combination of LiDAR technology and photography. LiDAR (Laser imaging, detection and ranging) is a method of using lasers and light reflection to take very accurate measurements, down to millimetres in some cases. Used on a feature in the landscape, it can produce a DEM with a grid spacing of 10 cm, or even less, to get very high-resolution models.

At the same time as the LiDAR is collecting these measurements, drones carrying cameras can take dozens of high-resolution pictures of the same feature. These cameras take pictures from different positions and angles but the same scale. If you know the scale of the photograph and the angle at which the photograph was taken you can use basic trigonometry to calculate size and distance between notable features. This is called photogrammetry. By using a computer with image matching software to identify even very small features in the landscape and the ability to run thousands of calculations in minutes you can combine hundreds of photos to create a very accurate 3D surface of whatever you have photographed.

If you combine the photogrammetry and the LiDAR data you can essentially recreate a feature in the landscape on the computer with accuracy down to a few centimetres. This is invaluable for studies of the landscape.

We’re still learning

Sometimes the oldest scientific methods are still invaluable even with the advent of modern technology. Looking at our landscape and understanding the stories that it tells us about the history of the world around us is something people have been doing for thousands of years. Modern day geology was founded on studies of landscape evolution and so much of what we know about out world started this way.

Yet, the landscape around us still has more to tell us. Both about our past and about our future. Modern technology allows us to recreate those landscapes on computers allowing us to learn so much more about how our world works. Likely, we will still be studying the landscape far into the future.

Leave a comment