There is a belief out there, when it comes to heat pumps, that they are inefficient, expensive and a symptom of the ‘climate change agenda’. They are being forced upon us when they don’t work, at least not as advertised, and will send energy bills sky high like so many other so-called ‘green technologies’.

This belief may be contributing to a reluctance for people to switch to heat pumps over the familiar, but high emission, options such as gas and oil burning boilers. However, there is still a question of how true this is. Are heat pumps really that bad? Is installing one a recipe for sky-high bills and regret? Or is it a question of people not understanding what heat pumps are and what limitations they have?

To start, let’s take a look at how heat pumps actually work.

Heat pump technology is proven

Heat pumps use the same basic technology that is applied in air conditioning systems across the world, as well as refrigerators. That is the power of compression and decompression.

To fully understand the process, we need to know two basic concepts. The first is that heat will always move from warm areas to cold.

The second is how molecules within substances interact with one another and with temperature.

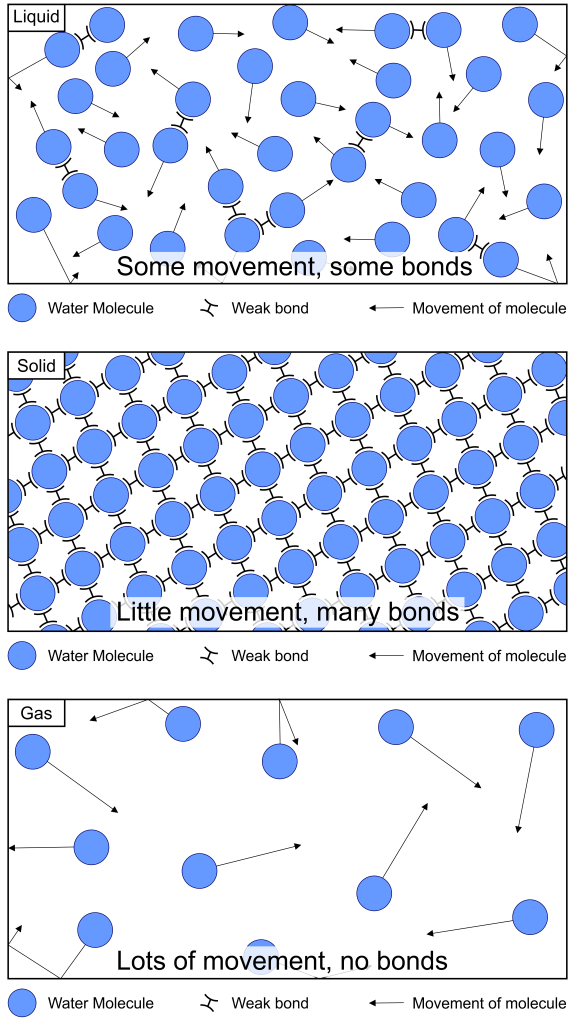

Everything is made up of molecules. Within every substance the molecules move around. They can hit one another and get ‘stuck’, forming a bond, which releases energy. Molecules can also move apart, breaking the bond, but to do this they use energy. This energy is usually some form of heat.

In any given material that is staying at the same temperature, the number of bonds being formed and the number of bonds breaking is about the same.

If you heat a material up, you are giving the molecules more energy. They start to move a lot more. The bonds between the molecules break more easily. They move further apart and hit each other less often, meaning fewer bonds are formed.

In contrast, if you cool a material, you are taking away energy. The molecules slow down. They collide more often, forming bonds. However, the energy created when the bonds form is lost due to the cooling, so they cannot break apart again.

Through heating and cooling we can change the state of a material. The simplest example of this is water. Liquid water can flow and move about. When you heat water up, you give the water molecules more energy. They spread out, break apart and eventually evaporate to form a gas. The opposite reaction is to cool liquid water. The molecules lose energy, they slow down, start sticking together and eventually freeze into solid ice.

The principal that forming bonds releases energy can also be used to generate heat.

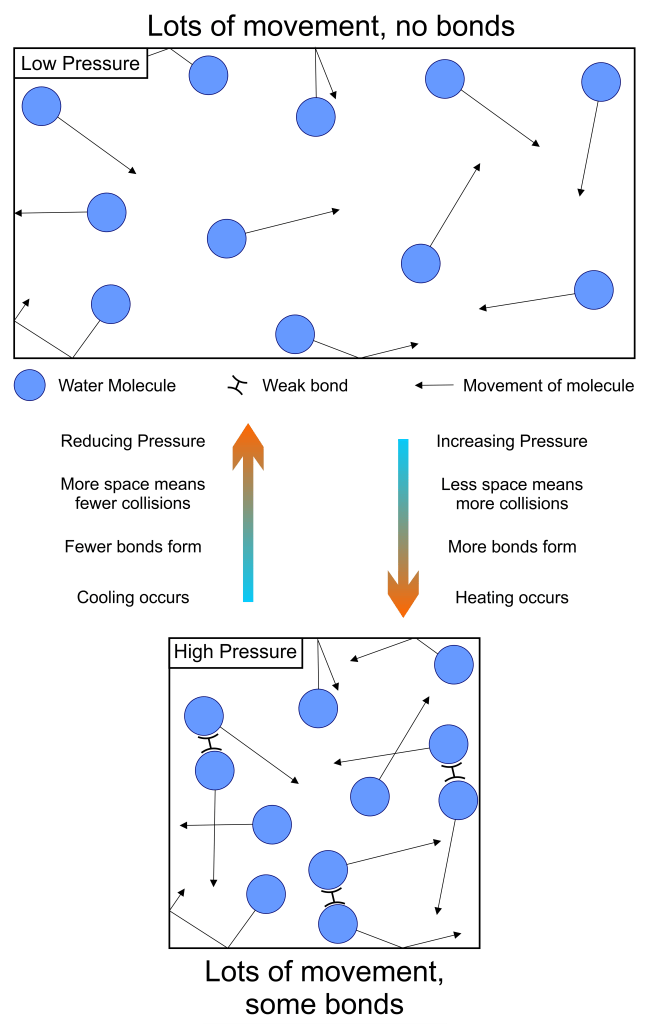

Start with a liquid that is being neither heated nor cooled i.e. there is no extra energy going into it and no energy being taken away. The liquid is stable. Every time a molecule of the liquid hits another and forms a bond, another bond within the liquid breaks.

Then, compress the liquid into a smaller space. There is the same amount of the liquid, it is just in a smaller container. Even though the molecules have not gained or lost any energy, they cannot move as freely as before. They collide more often and, in turn, form more bonds. If you compress the liquid enough, then they cannot break those bonds even though they have the energy, because there is nowhere for them to move to.

In short, more bonds are being formed than are being broken. More energy is being released than is being used. In this situation, the excess energy takes the form of heat and the temperature starts to rise.

The reverse situation is also true. A compressed liquid can be put into a larger space; decompressing it. The molecules within it can suddenly move a lot more freely and all those extra bonds that were forced to form start to break. As there is now more space, there are fewer collisions happening so fewer bonds forming. More bonds break than form, which means more energy is used than is released. The liquid then cools.

This is the principal by which heat pumps work.

By design, heat pumps are efficient

While there are a number of different types of heat pump, there are two major types: air-to-water and ground-to-water heat pumps. They work in similar ways, and are only really different in the first step. In air-to-water heat pumps, they draw heat from the surrounding air to start the process. In ground-to-water, the initial heat comes from the ground. Ground-to-water heat pumps are generally going to be more stable and consistent, because the temperature of the ground varies a lot less than air temperature, but they are more expensive because they require pipes to be installed below ground to capture that heat.

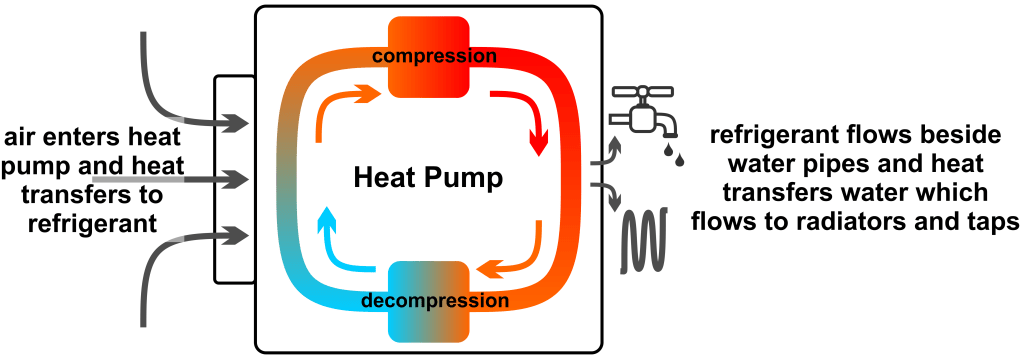

The heat source, be it air or ground, increases the temperature of a chemical mix within the heat pump called the refrigerant. The exact mix depends on the heat pump manufacturers and government policies, but doesn’t really influence the process. The refrigerant, once heated, passes into a chamber or series of pipes where it is compressed. As it is compressed it starts to produce heat.

The compression requires electricity as an energy source. However, because the refrigerant is already heated by the air or the ground, it requires less energy to compress than it produces. Less electricity goes into the heat pump than it would need to heat the refrigerant directly. The warmer the refrigerant before compression, the less electricity required.

After the refrigerant is compressed and it becomes hot, it is then pumped through pipes that are alongside either water pipes or a water tank. The heat transfers from the hotter refrigerant into the cooler water. This water can then be used in traditional water heating systems, such as radiators and under-floor heating systems, or it can come out through taps and showers for hot water.

The refrigerant is then passed into a decompression area, where it is allowed to expand. The molecules are no longer hitting each other as often, so it stops producing heat and instead cools down. The cool refrigerant can be passed back to the outside, to draw more heat from the air or the ground.

Interestingly, because the system is a closed loop, some models of heat pump can be put into reverse. Heat from inside a house can be drawn into the heat pump through the usual heating system and then expelled by the heat pump into the air through decompression. This will then cool the house. The exact same process is used in most air conditioning systems, but this uses the same system for both heating and cooling. Very useful in a country which has not traditionally needed air conditioning, but is seeing increasingly hot summers during climate change: for example, the United Kingdom.

Heat pumps have limitations

Of course, as with many things, there are downsides to heat pumps. That which makes them most efficient, can also be the cause of most of its limitations.

Heat pumps work best in moderate climates. Obviously, if the air temperature drops too much, or the ground freezes, there is less heat available to transfer into the system. Although most heat pumps can cope admirably with moderate winters, because there is still energy in the air, the colder it gets the more electricity it needs to compress the refrigerant. If it gets too cold, the refrigerant will freeze in the pipes and stop flowing altogether. Engineers are working on this, to produce heat pumps that work in colder environments, but for now this is a limitation.

Heat pumps also generally run at much lower temperatures than the most common alternative – the gas boiler. This is because to get higher temperatures, you need either much warmer air temperatures, at which point you probably aren’t running the heating system, or you need more energy from electricity. The lower the temperature the heat pump runs at, the more efficient it is.

Gas boilers, on the other hand, run much hotter and can be fired up more quickly. You can’t control the temperature the gas burns at, that is a fixed temperature, which means it’s more difficult to control the temperature of the water it heats. Trying to lower the temperature of the water, so the boiler runs cooler, is actually less efficient and is a waste of gas. In that way, a gas boiler is meant to run very hot for a short amount of time, heating the house quickly, and intermittently. Because of the excess heat, they can work with small radiators, but this can lead to less consistent heating over the whole house.

Heat pumps are meant to be run for prolonged periods of time and work best with large radiators or under-floor heating. They can give more consistent heating, but also are more vulnerable to the issue of insulation.

A powerful gas boiler in a house with poor insulation is still capable of heating the entire house. It’s inefficient, especially when the boiler stops firing, as a lot of heat is lost, but it is still functional. A heat pump, running at much lower temperatures, in a house with poor insulation, may not be able to heat the house sufficiently as heat is lost faster than it can produce it.

Furthermore, as heat pumps can’t be fired up as quickly and don’t get as hot, they can have issues with heating water for sinks and showers. You will probably either need an additional convection heater – which works the same way as most electric kettles – or a hot water tank. If you already have a water tank, you probably won’t notice the difference, but many modern gas boilers are combination boilers. These can start up so fast that they can heat water on demand and don’t need a separate water tank.

Heat pumps are expensive

These are the major engineering limitations of heat pumps: decreasing returns in extreme cold, poor heating in poorly insulated houses and slower heating of water.

Two of these, however, are getting better and better with every passing year as engineering of heat pumps improves – in a few years we may well get heat pumps that can work in even very cold weather, or can heat water as quickly as a gas boiler. The third is an issue we should be striving to fix anyway; a lack of insulation vastly increases energy bills and can cost someone hundreds each year because of the heat loss.

The final major limitation for heat pumps is cost. Unfortunately heat pumps are more expensive than gas boilers right now, at least to install. The costs of running a heat pump vary wildly and depend entirely on the local average temperatures, how good a house’s insulation is, what sort of radiators they have, how big the house is and what energy tariff is available. However, many people will in fact find that heat pumps are cheaper to run than gas boilers.

There is also help when it comes to the installation costs. Many countries are running schemes that give out grants or subsidies for heat pumps. As an example, the British Government is currently offering grants for homeowners who switch to heat pumps up to a value of £5000. However, adoption of heat pumps since this policy was announced has been poor. In the first ten months of the scheme, from May 2022 to March 2023, around 15,000 applications had been made for the grant with around 10,000 redeemed and paid out (UK Gov website, 2023). That is about half of what was allocated for the entire year.

Finally, the price of heat pumps is dropping. This is always the case with new technology – wider adoption and demand means more investment. More investment means finding cheaper ways to produce the technology. We have seen it happen with electric cars. They have both been getting cheaper and improving in range and efficiency because more people are buying them.

Heat pumps are the future

The difficult truth is this: yes, heat pumps are not a perfect solution. There are people out there with old homes that are difficult to properly insulate that won’t get the most out of a heat pump. There are people who straight up cannot afford to install one, even with a government grant.

However, what is the alternative? To continue to rely on gas boilers and other heating systems that use fossil fuels?

We need to cut emissions drastically if we are to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. That isn’t an ‘agenda’ it is solid fact, backed by decades of scientific research from all over the globe. Buildings, both houses and businesses, contribute about 6% to our global emissions, according to the IPCC (IPCC, 2023), with the majority of that coming from the energy they use. That doesn’t just refer to the electricity to turn on the lights and run our computers, it’s also the gas and oil we burn to heat our homes.

Combining switching to a heat pump, switching to renewable sources of electricity and improving energy efficiency through proper insulation will drastically cut those emissions. It is one of the biggest ways that individuals can cut their own emissions.

Don’t believe the horror stories

Installing a heat pump is not a recipe for instant regret. It requires research. It requires understanding how they work and how different they are to the systems we are used to. However, for many people it is simply one of the best things they can do; for themselves, for society and for the environment.

If you can’t afford a heat pump: be patient. The price will come down. More options will become available in the next few years.

If you can afford a heat pump: do the research. Find out if your house or business is one that is easily adapted to heat pump use and if it can, seriously consider the investment. Sure, you could wait a few years, hope the price comes down and save yourself money. However, the more people who wait, the longer it will take for the price to fall.

We can see a future of efficient, low emission heating for everyone, but it does require people to start down the path, even if it is rocky at the outset. The more people who walk it, the smoother the path will become.

Leave a comment