“We have to keep global warming below 1.5˚C!” is the rallying cry of climate scientists the world over, quoted again and again in articles that insist our planet is heating up at unprecedented rates. More than 1.5˚C will spell disaster for everyone and everything.

At the same time, however, snow storms in January and February 2023 have buried parts of California, even outside the mountains. Record breaking cold snaps have been reported across Afghanistan, Japan, South Korea and parts of China. If the Earth is warming so much, why are we seeing places get colder?

The truth lies somewhere between our complicated climate system and the language that has been used to describe global warming and climate change to the public. The best place to start is with what global warming and climate change actually are.

Global warming vs climate change

When used by scientists global warming refers, specifically, to the average global surface temperature as measured by hundreds of climate stations across the world for the last 150 years or so. These stations have been collecting temperature data almost continuously for organisations like the MetOffice in the UK, and NOAA in the US, as far back as the early 1800s.

The overall trend of global average temperature has been for surface temperature to rise over time, with temperatures rising much faster from the late 1900s to today. Temperatures have been rising much faster than any known period of natural temperature change (read more here). Scientists point to this as a very simple and compelling explanation of what humans have been doing to our atmosphere and planet.

On the other hand, scientists understand climate change to be the effect of global warming. We do not have one single global climate. Everywhere in the world has its own climate and weather and these all react to global warming differently. In order to predict how the climate will react to different amounts of warming in different places, scientists use computer models which mimic the processes that are taking place.

Climate modelling is complicated

Our climate system is made up of thousands of different parts all interacting with each other every single day. Temperature, air pressure, humidity, whether there is sea or land in a given area, how high that land is, what time of the year, if there are any solar events, what the tides are like, how much dust is in the air, what the weather was like a week ago… all of these things combined and more determine the weather on any given day. The climate is then the day-to-day weather averaged over a long period of time, usually about thirty years.

There is no supercomputer on earth that could run a model for the whole planet that takes into account every single one of these factors. Scientists have to make decisions on which are the most important for the question they want answered. They also need to find the simplest way possible to mathematically represent each of the most important factors. The simpler the calculations the computer needs to perform, the more calculations it can do and the faster it can do them.

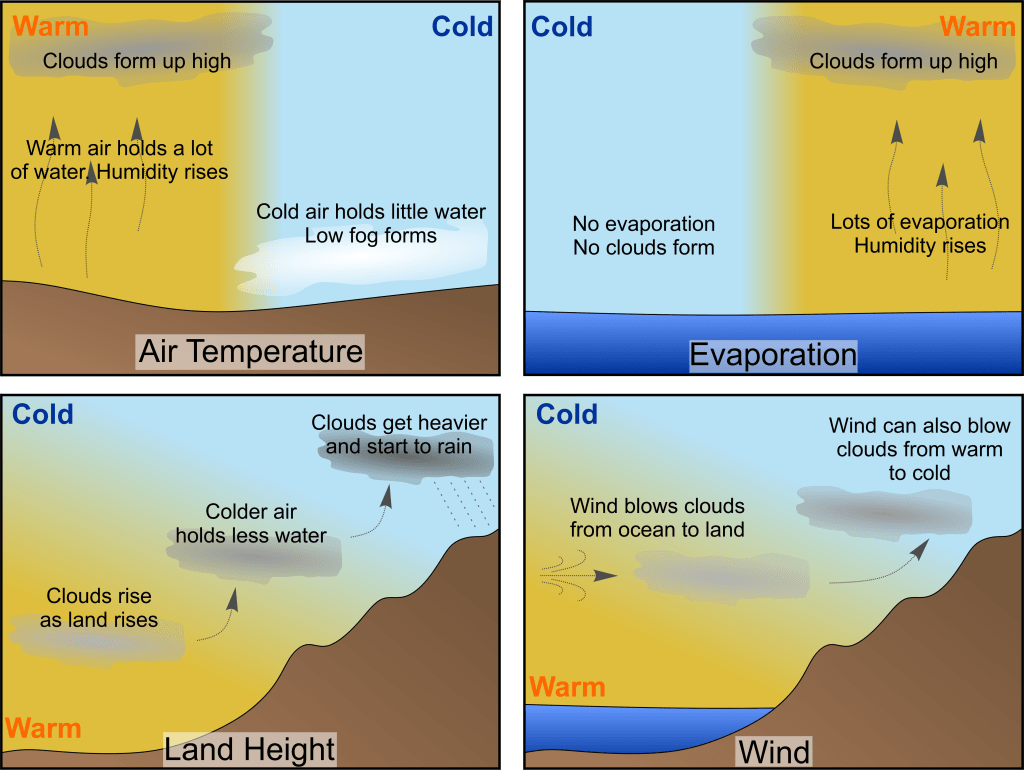

For example, say scientists want to know how a warming trend in global average surface temperature affects rainfall. The amount of rainfall is controlled mainly by the temperature of the air, how much evaporation is taking place, the height of the land, which way the wind is blowing and how strongly. Of these, the global average surface temperature strongly affects the air temperature and evaporation, with a smaller impact on wind direction and speed.

Thus, scientists might choose to use fixed numbers for the height of the land and a very simple calculation of wind, because these will not change as much as air temperature and evaporation. This means they can add relatively complex, but more accurate, calculations for air temperature and evaporation without making the model too complicated to run. They will then run the model using a historical dataset of temperature changes and compare the results to historical records of rainfall. In this way we can see how accurate the model is.

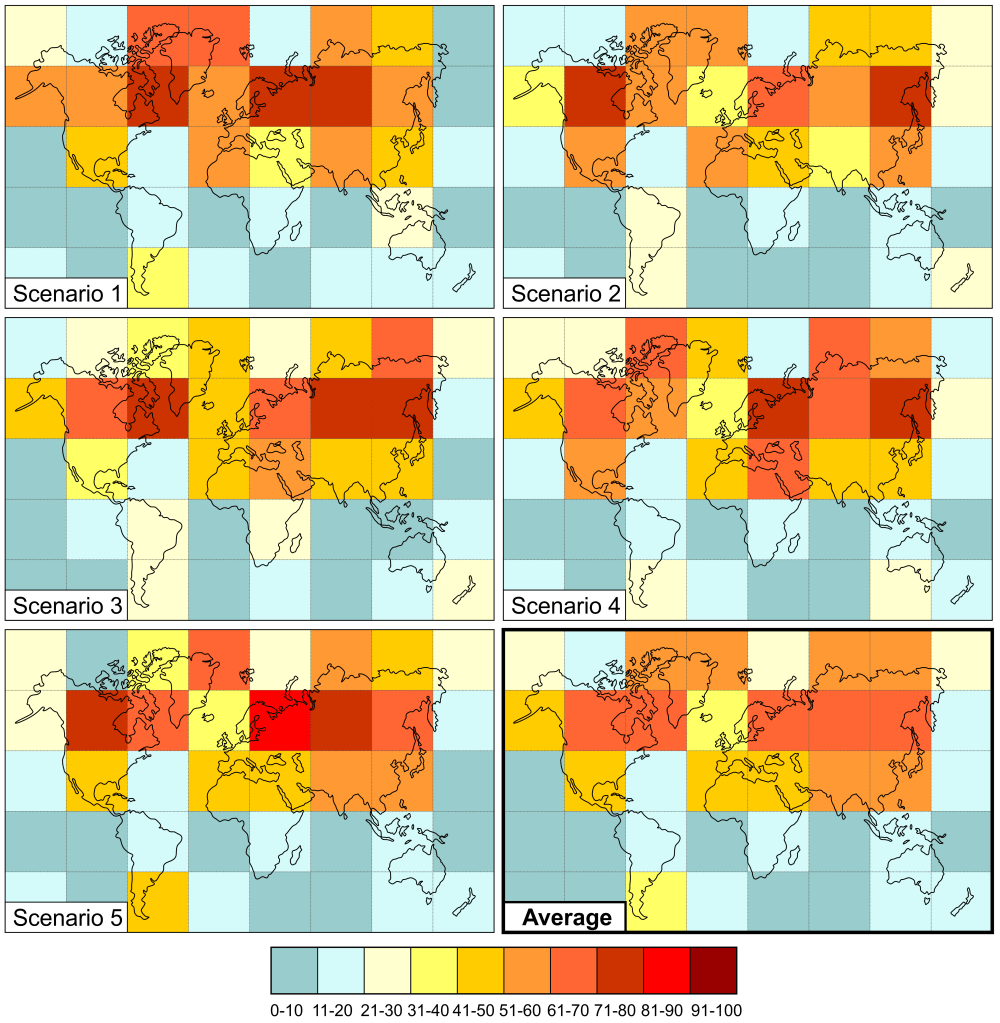

Once the model accurately produces results for the historical dataset, it is then used to test a variety of warming trends going into the future. In current scientific research, a model is likely to be run dozens or hundreds of times with very small variations in all the inputs and some degree of randomness inbuilt. Every result is then collected together and compared, producing a map that shows the most likely result for a given warming trend, usually with a 95% confidence interval.

This does not mean that the scientists’ model is exactly what will happen in the future. It is a projection of the most likely scenario and not a hard, fixed prediction. There is a degree of uncertainty built into every model, because some of the processes must be simplified in order to run the program. This is why scientists will generally use models to look at trends, rather than exact figures.

However, even with the uncertainty modern climate models are very good at accurately reproducing past climate data and they are improving every year.

Climate models are accurate

When assessing the accuracy of models it is important to take into account the type of model and how far into the future is it projecting.

Regional climate models, which primarily cover a small area, such as a country or a state, can be used to look at very small time increments of days or even hours. Their principal use, therefore, is in weather forecasting. As the area covered is small a lot of the larger processes can be simplified. That gives more freedom to model small details and also means the models can be run much more quickly.

Testing the accuracy of weather forecasting is relatively straightforward and has improved massively in the last couple of decades for two major reasons. Firstly, with weather forecasting scientists can very quickly compare what was predicted with what actually happened. Errors can be identified and fixed for the next forecast. Secondly, because weather forecast models can be run in a short space of time they can be updated with real-time data from satellites and weather stations very quickly. If a storm starts to form out in the ocean within a few hours the weather forecast will include that new storm.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) claims that their 5-day weather forecasts are 90% accurate and their 7-day forecasts are 80% accurate (NOAA SciJinks, 2023). The UK’s MetOffice states that 92% of their next-day forecasts of temperature and wind speed are within 2˚C or 5 knots (MetOffice, 2023). However because of the strong day-to-day variability in weather, accuracy drops off dramatically after about 7 days.

At the other end of the scale, global climate models cover whole continents, or the entire planet, and will run decades or even centuries into the future, looking at long-term trends. It is far harder to assess the accuracy because they do project so far into the future and few scientists will put an exact number to the accuracy. However, that does not mean that the models are inaccurate.

The earliest computer global climate models are from the 1970s and 80s. This is when scientists really started to understand the long-term climate and started to grow concerned about the warming of the global average surface temperature. According to core records and other measures of historical climate, scientists thought that the warm period humans have been enjoying should have been drawing to an end; however they discovered the opposite was happening. The Earth was suddenly heating up instead.

Since then, however, we have four decades of both climate model results and measured climate and weather patterns that we can compare to assess the accuracy of the models. So far, many of the early climate models have proven to be relatively accurate within the limitations of the models themselves (Hausfather et al. 2019).

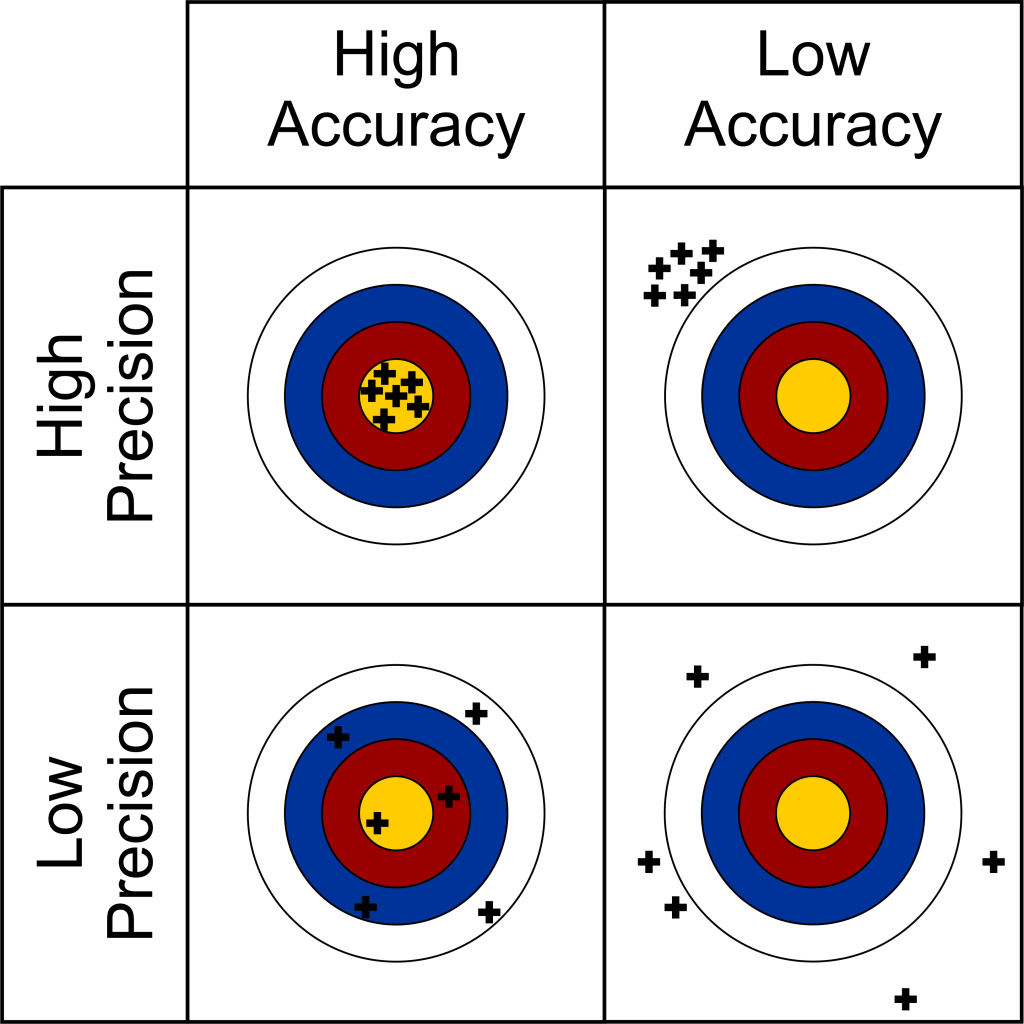

Accuracy is not the same as precision

The issue with climate models hasn’t typically been the accuracy. Some models have proven to be wrong, but most of the errors with early modelling haven’t been a matter of accuracy but of precision.

Accuracy is how correct an answer is. Precision is how detailed the answer is.

Ideally, we want climate models that are both accurate and precise.

The earliest climate models were run on computers that weren’t powerful enough to really handle all the calculations to make a very precise model of the climate system. They could predict very broad trends such as the effect of global temperature rise on the polar ice caps and the sea level rise that follows. However, they could not say which parts of the ice sheets would melt first, or which glaciers were most at risk or even the exact amount of sea level rise.

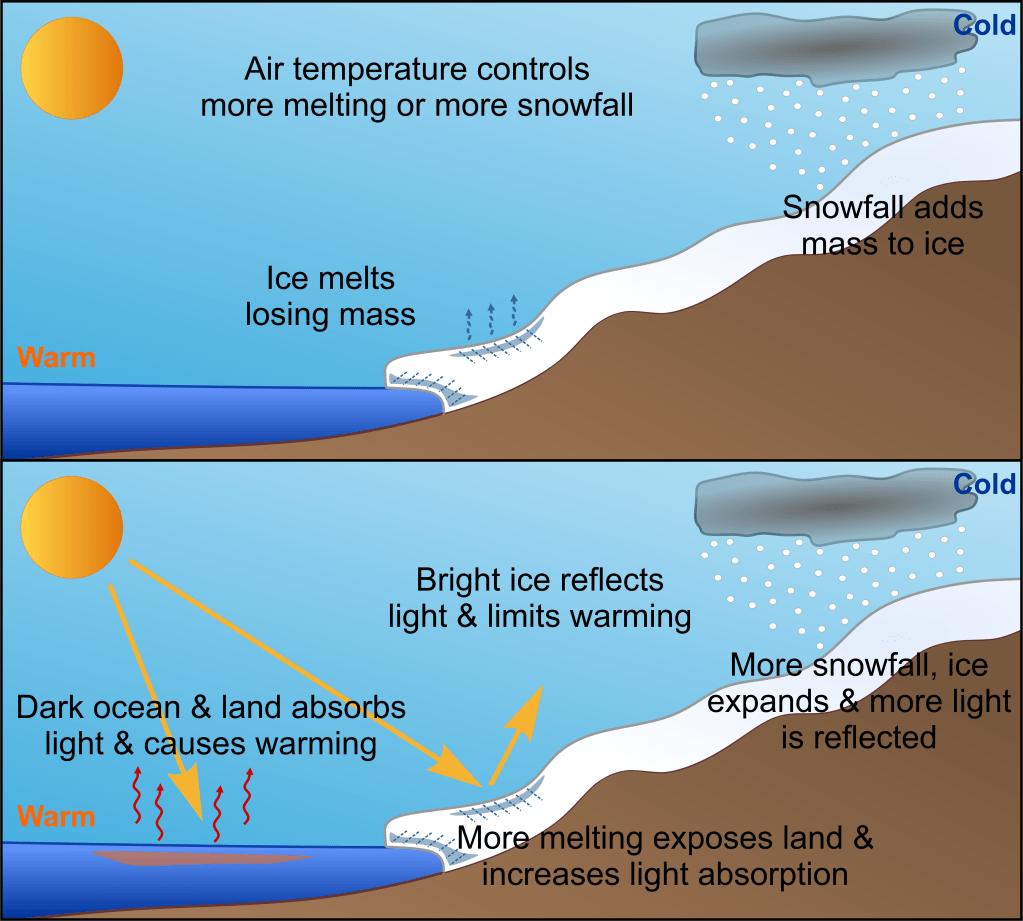

The broad relationship between global temperature, ice cover and sea level is relatively straight forward. It combines average surface temperature, the melting rate of ice compared to how much snow is falling on the ice and what’s called the albedo effect. That is how bright the land surface is. Brighter land surfaces reflect light with a minor cooling effect and duller or darker surfaces absorb light producing more heat. With less ice more dark land area is exposed and more heat produced from light absorption.

and albedo on ice sheets

However, while temperature, melting rate and albedo are relatively easy to model on a global scale, snowfall is not. You need an entirely separate model to predict how snowfall will change with changing temperatures. This is where the precision starts to factor in and affect accuracy.

Melt rate and albedo have stronger effects on ice than snowfall does, so the general trend of global warming has led to increased loss of ice worldwide. The early models predicted this trend and it is one that has been observed at hundreds of glaciers across the world and in the loss of sea ice around the Arctic and Antarctica. However, contrary to the predictions a small number of glaciers initially grew in size before eventually starting to retreat.

This is because while temperatures have been getting warmer, certain parts of the world have been getting wetter. There has been more snowfall that countered the effect of increased melting of the ice to a certain point before melting became overwhelming.

The earliest climate models have been proven to be accurate. However the early models are not and never were very precise.

Should models be correct or useful?

It is important that climate models are not viewed as hard, exact predictions of future climate because that is not what they are. They are tools and a way to look at likely trends in future climate.

“All models are wrong, some are useful.”

George Box, 1976

Imagine an early climate model from the 1970s that suggested global temperatures would reach 1.5˚C above the pre-industrial average in 2020. It can now be said the model was ‘wrong’ in that the exact figure of 1.5˚C was not reached. However, that same model did predict the rampant global warming experienced over the last decade and the rate at which temperature has increased, within a reasonable degree of uncertainty.

The model might not have been precise, but it was not inaccurate given the constraints of the technology and, crucially, it was useful. The model not only conveyed the trend in global warming, it gave scientists cause to investigate further and inform the public of what was happening and acted as a base for newer, better models to be built on.

Just as weather forecasts have improved dramatically over the last couple of decades, so too have global climate models. Not only do we have a lot more data on climate we can use to fine tune the models, scientists now have much greater access to powerful supercomputers. Supercomputers can run much more complicated models, much faster.

Scientists can now combine multiple models into one, so as to accurately represent how two or more parts of the climate interact with one another. They can much more easily spot errors in models and fix them, because it is the work of a few weeks, instead of several months, to run a full set of variations for each model. Models are both more accurate and more precise.

Modern climate models may not be ‘correct’ in that the chances are the exact figures for ‘temperature’ or ‘sea level rise’ or ‘year’ are not going to be matched. However, when looking at probabilities and percentage changes instead, there is reasonable certainty that they will be accurate enough. Even if they aren’t, they will definitely be useful.

That’s all well and good for scientists, but that does this mean for everyone else?

We need to look at all the evidence

As with much of science in general, it is important to take into account all of the available evidence. This means not just weather data recorded from the last 150 years, but all the data from geological history and the climate models.

Practically speaking, this means that we can’t just look at the cold snaps in California and across Asia in early 2023 and use them to claim global warming isn’t happening. Not when, at the same time as these extreme cold events, parts of the world were seeing the mildest winters on record. January 2023 saw eleven countries in Europe reporting the hottest January on record with temperatures up to 4˚C higher than previous records.

Global warming and climate change do not meant the same thing. Global warming causes climate change. Climate change is not going to be the same everywhere or at the same time and the more recent climate models show that.

The winter storms, in this case, have been attributed to more common extremes of temperature and weather. Climate models have been predicting that global warming will lead to an increase in extreme weather events for years. They predict more hurricanes and more of them reaching category five. They predict more droughts which lead to forest fires and more flooding because of extreme rainfall.

And yes, climate models predict more winter storms and record-breaking cold temperatures.

Climate modelling is complicated. It is entirely understandable to be confused by them. The complicated nature of models is why they are so often misunderstood or misused.

However, to dismiss them entirely is not helpful to anyone. Climate models serve an important role in climate science, even if sometimes they are out by a few degrees.

Leave a comment