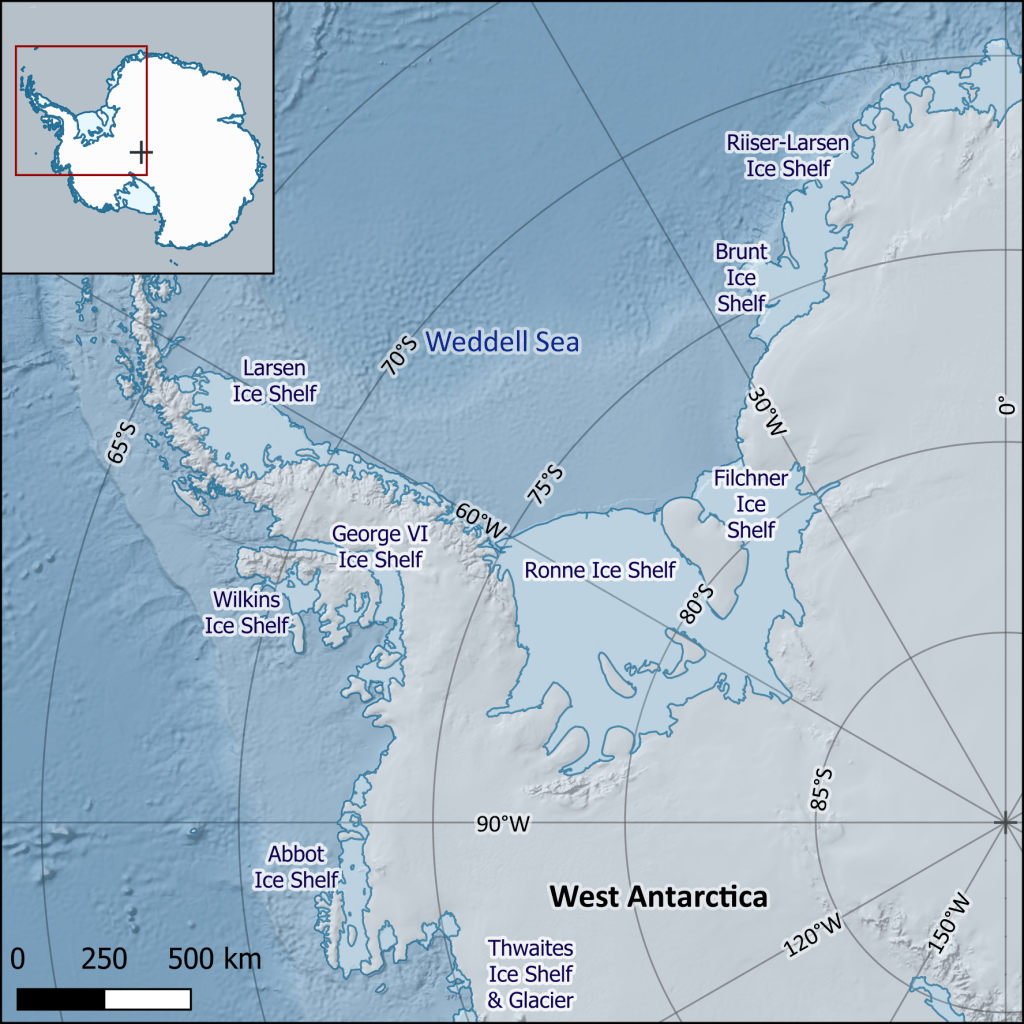

In late 2015 a huge crack was observed in the Brunt Ice Shelf of western Antarctica. The crack gained fame when it drove the British Antarctic Survey to move their entire research base 23 kilometres inland. On 22nd January 2023 this crack broke through the last few kilometres of ice to snap off a huge iceberg the size of Greater London.

The new iceberg, named A81 (video, BAS 2023), joins the ranks of other ‘mega’ icebergs that have broken off the ice shelves around Antarctica in the last two decades. These ‘mega’ icebergs, often the size of cities or even bigger, are part of a larger story about the vast areas of floating ice in the seas around Antarctica. These areas of floating ice are called ice shelves, many have existed for tens of thousands of years, and they help keep Antarctica the continent of ice.

The story of ice shelves and their ‘mega’ icebergs starts with how ice shelves are formed and why.

How are ice shelves formed?

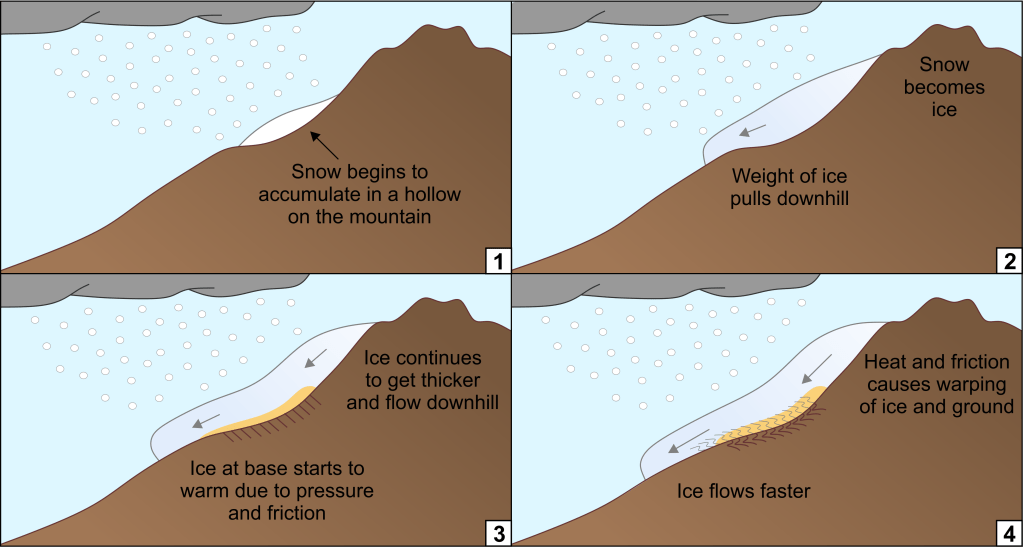

Antarctica is covered by ice. This ice is divided into two ice sheets, one on the eastern side of the continent and one on the west. These ice sheets are not stationary blocks, sitting on the land. Just like rivers, ice flows from the mountains down to the ocean.

Although ice is technically a solid, it does actually flow when put under enough pressure. Pressure creates friction which creates heat. A lot of solids when warmed up don’t immediately melt. Instead, they will go through a phase where they become bendy and easy to warp.

Consider glass blowing or metal forging as examples of this, the glass and metal aren’t liquid but they are hot enough to be shaped. Ice is just the same. At the base of an ice sheet, the weight of thousands of tonnes of ice above will cause the ice to start to warm and to bow and buckle.

Ice sheets form high up in mountainous areas, on slopes. Gravity is trying to pull it down the slope as soon as it starts to form. Eventually the mass of ice is big enough that it will start to slide. As it gets bigger, the weight creates pressure and ice at the base of the ice sheet starts to soften and warp. At the same time, the ground underneath the ice is also placed under huge amounts of pressure and, in a very similar way, will start to deform also. This allows the ice to flow more easily.

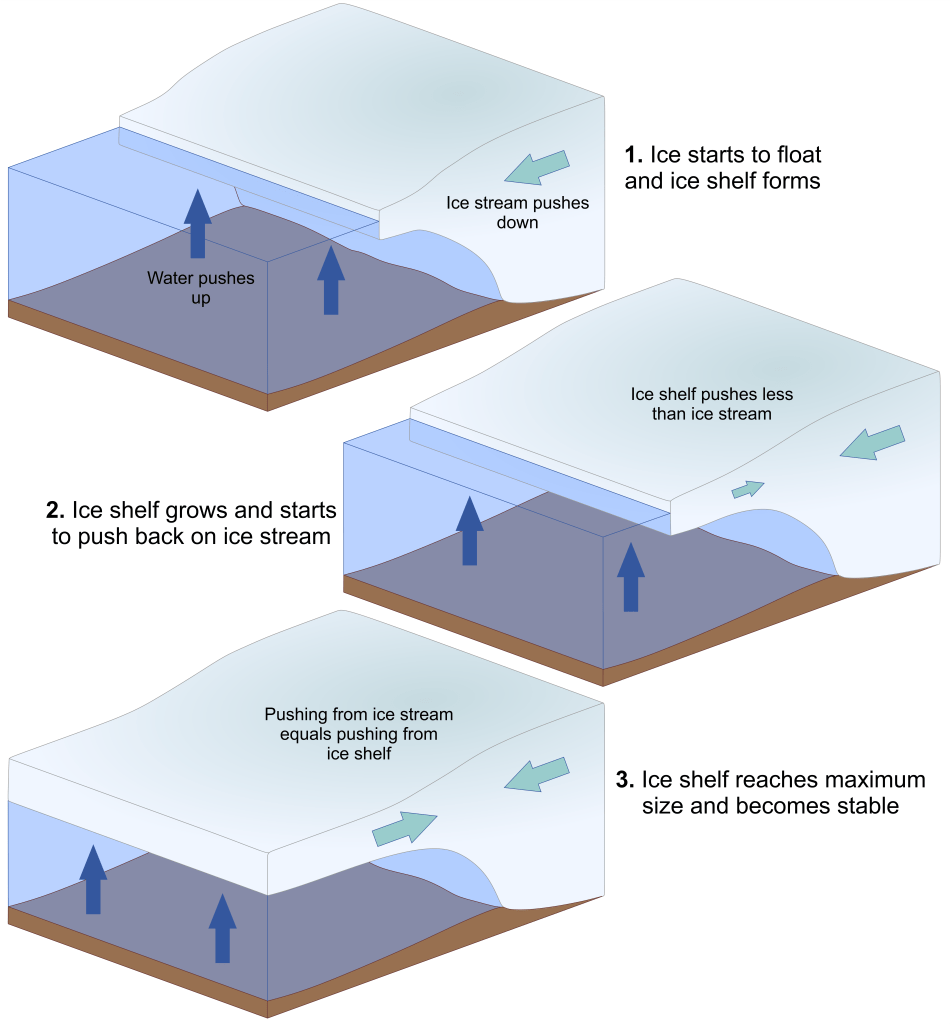

So what happens, then, when the ice reaches the ocean? Well, as most people know, ice is less dense than water and it floats. The ice that reaches the water is still being pushed from behind by the rest of the ice sheet at the same time as it is being pushed up by the water. This creates big, flat chunks of ice still attached to the ice sheet but sticking out into the ocean like tongues. These are called ice shelves.

Ice shelves control the fate of ice sheets

The existence of ice shelves protects the ice sheets. The flow of ice slows down when it reaches water. This is because the buoyancy of the ice on the water counters the pull of gravity. The only thing pushing an ice shelf further out into the water is the ice behind it, flowing down from the land.

However, as the ice shelf grows its sheer bulk makes it harder to move. Eventually, the ice flow from the land cannot push the ice shelf any further out to sea. The bulk of the ice shelf causes the flow of ice to slow even more. A slower flow of ice is more stable. More ice builds up and ice sheets can then persist on land for tens of thousands of years.

If an ice shelf loses too much bulk, too quickly, the flow of the ice sheet on the land would accelerate dramatically. Huge amounts of ice would move from the stable, mountainous areas to much lower land. Lower lying land tends to be warmer and this causes ice to melt from the ice sheet itself.

Ice shelves become icebergs

All ice shelves are constantly being destroyed and replaced. In a stable ice shelf there is a balance between the ice being lost to the sea and ice flowing into the ice shelf from the land.

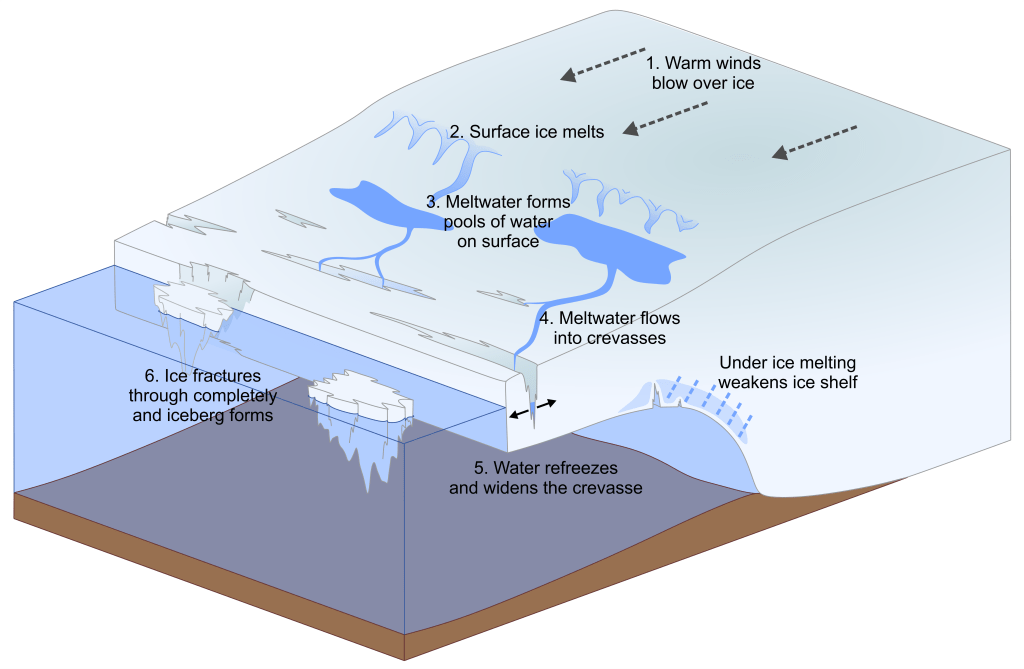

Ice is lost from ice shelves in two main ways. The first is melting, either from the water underneath the ice shelf or from warm dry winds that blow across the surface. Compared to the combined size of the ice sheet and ice shelf, only a small amount of ice is lost this way. However, melting on the surface of an ice shelf creates pools of meltwater.

At the same time the flow of ice pushing on the ice shelf creates vertical cracks, called crevasses, in the ice surface. The meltwater on the surface of the ice flows into the crevasses, where it re-freezes and expands forcing the crevasse to widen. Eventually the crevasse becomes so big that it breaks through the ice entirely. Large chunks of ice snap off and fall away into the ocean, creating icebergs.

This process is called iceberg calving and it is how most ice is lost from ice shelves.

Iceberg calving can tell us a lot about the health of the ice shelf and, in turn, the health of the ice sheet. If more ice is being lost through calving than is being formed in the mountains, then the ice sheet is losing mass. It’s getting thinner.

Warming of both the sea and the air around ice shelves can cause iceberg calving to increase. The warm winds which cause most melting become more common and, in turn, cause more meltwater to flow into crevasses. The calving of ‘mega’ icebergs is strongly associated with years that are particularly warm and windy. In the most extreme cases, the ice shelf becomes so unstable from the number of crevasses that it shatters like glass.

This has already happened twice in the Weddell Sea and is expected to happen again, all across Antarctica.

Antarctic ice shelves are disintegrating

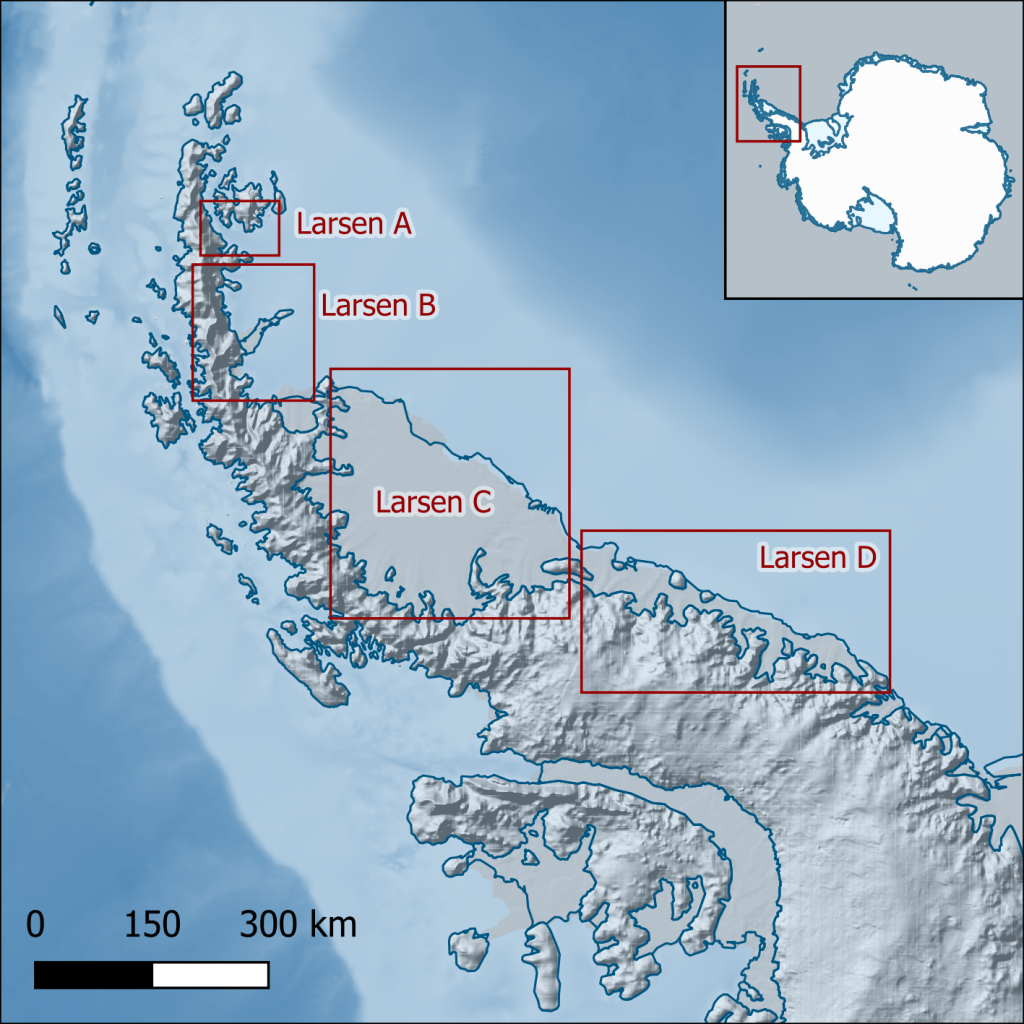

On the opposite side of the Weddell Sea to the Brunt Ice Shelf sits the Larsen Ice Shelf. This ice shelf stretches thousands of kilometres along the side of the Antarctic Peninsula. The Larsen Ice Shelf is so large it is commonly split into four sections, A, B, C and D.

At least, this was what the Larsen Ice Shelf looked like for thousands of years. All that changed in 1995.

In January 1995 during a particularly warm summer, the Larsen Ice Shelf saw extremely high rates of melt. The Larsen A part of the ice shelf started to rapidly form lots of icebergs. Calving reached a critical point and, within a few weeks, the whole ice shelf collapsed.

The sea around where Larsen A had been was filled with icebergs which quickly dispersed leaving open sea where there had once been an ice shelf.

In 2002 the same thing happened again. A particularly warm summer led to an increase in warm, dry winds blowing over Larsen B (Wille et al 2022). Huge pools of meltwater formed and then flowed into crevasses. Calving increased dramatically and within three weeks, Larsen B disappeared entirely.

Larsen B covered an area about the size of Luxemburg. It had existed for at least 12,000 years. Immediately after Larsen B collapsed, ice that had been flowing into the ice shelf started to speed up. The warming of the Weddell Sea area over the last few decades means that the ice is melting faster than a new ice shelf can be formed.

In recent years attention has turned to Larsen C and whether it will follow its neighbours, if warming continues.

Larsen C is the largest of the four parts of the Larsen Ice Shelf. This part of the ice shelf is over 100,000 years old and is protecting ice equivalent to about 2 cm of global sea level rise. For context, scientists believe global sea levels are currently rising about 1 cm every 3 years.

The same summer that the British Antarctic Survey realised the Brunt Ice Shelf was starting to crack, scientists discovered a huge crevasse in Larsen C. The crevasse grew quickly during the next year and in July 2017 it broke through the ice shelf completely to form a ‘mega’ iceberg. This iceberg, named A68, was the sixth largest iceberg on record and almost as large as the island of Cyprus.

Although the calving of A68 was not immediately followed by the same patterns seen in Larsen A and B there is still cause for concern. Extended warming on the Antarctic Peninsula will lead to increased melting and calving of the ice shelf. The ice shelf will thin as the lost ice is not replaced quickly enough. This makes the ice shelf more vulnerable to particularly warm years. Neither the Brunt Ice Shelf, nor Larsen C has reached the point of no return. The increased calving of ‘mega’ icebergs is a warning sign and not the start of collapse. However, they are warning signs we cannot afford to ignore.

We can’t predict when ice shelves will collapse

We don’t yet have the ability to predict the winds which lead to increased melting, increased calving and, eventually, ice shelf collapse. We know they are linked to warmer than average years and appear to be occurring more often as Antarctica warms. However, warmer-than-average years are not easy to predict either.

What we do know is that these winds will continue to blow. As Antarctica warms, the ice shelves protecting the coastlines thin. The thinner the ice shelf the more likely it is that the next warm and windy year will be its last.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is famous because moving a research base makes for an interesting story. The Larsen Ice Shelf gets news coverage because its history of collapsing is dramatic. Yet, neither of them are the biggest or most threatening ice shelf on the brink of collapse.

Well away from the Weddell Sea and its drama, sits the Thwaites Glacier and Ice Shelf. Scientists expect Thwaites Ice Shelf to collapse within the next ten years, perhaps even as soon as five years from now. After that, Thwaites glacier will follow. If Larsen C collapsing will cause 2 cm of sea level rise, the collapse of Thwaites will lead to 65 cm of sea level rise over the next century.

There is no way to know if Thwaites can be saved, or if it is already too late. For this reason, Thwaites is sometimes called the ‘doomsday’ glacier.

The calving of the A81 iceberg in January 2023 is something scientists have seen coming for years. The presence of the British Antarctic Survey means the Brunt Ice Shelf is one of the most well monitored ice shelves in Antarctica. In that respect, the final break isn’t as dramatic as it could have been.

However, Brunt Ice Shelf and A81 are only one part of a story that is playing out on repeat across Antarctica. Next time, we might not have almost eight years of warning. We might, instead, only get three weeks.

Leave a comment