If you have read an article or listened to someone talk about West Antarctica recently, it was probably about how the ice is all going to vanish overnight. Names such as the ‘doomsday glacier’ are mixed with words like ‘imminent collapse’ and others meant to inspire a fear of catastrophe. Yet, surely these headlines and comments are just clickbait?

West Antarctica is covered by ice that is tens of kilometres thick. Even in a warming world, that much ice cannot just vanish in an instant, surely? Even if it could, West Antarctica is no different to the rest of Antarctica or Greenland, which are surely just as affected by a warming world as West Antarctica. No one describes them as the herald of our doom.

Well, that is actually an interesting story. West Antarctica actually is different to the rest of Antarctica and Greenland in one very simple way. That simple difference, however, changes everything about the ice and how it reacts to a warming climate.

What is West Antarctica?

Everyone knows Antarctica is covered in ice. What you might not realise is that the ice isn’t just one huge slab dropped onto a flat piece of land that just sits there, doing nothing.

Antarctic ice is made up of two huge domes of ice the size of continents, called ice sheets. These ice sheets appear to just sit there from a distance, but they are actually flowing very slowly towards the ocean. The movement of ice and how it interacts with mountains and valleys creates a host of different features.

Some of these include ice caps, which sit on the sides of mountains and constantly push ice down the slope. Glaciers and ice streams are rivers of ice which carry that ice from the ice caps down to the ocean. Ice shelves are floating masses of ice that stretch out into the ocean whilst remaining stuck to the land.

The two Antarctic Ice Sheets are split into the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and the West Antarctic Ice sheet, commonly abbreviated as EAIS and WAIS. Combined they cover over 14 million square kilometres and at the thickest the EAIS reaches 4.7 kilometres. That’s nearly 6 Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world, standing on top of one another. There is also the Antarctic Peninsula, which has its own unique system.

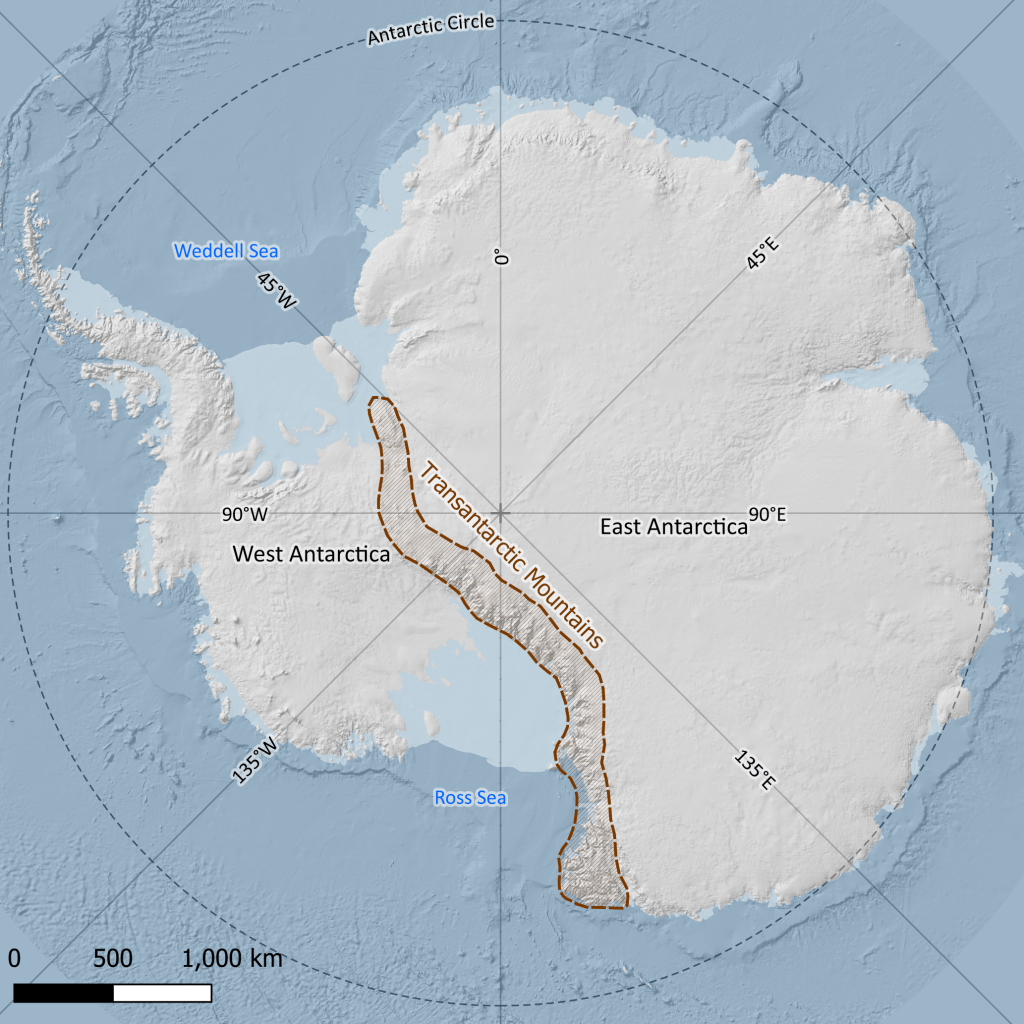

The two ice sheets are separated by the Transantarctic Mountains. These mountains are almost entirely buried by the ice, so that only the very peaks appear on aerial photographs. The side of the mountains that sits mostly in the eastern hemisphere is East Antarctica and is approximately twice the size of the side that sits in the western hemisphere. Although they sit next to one another, the East Antarctic Ice Sheet and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are very different. That is because the land they sit on is very different.

A tale of east and west

In order to look at the ground underneath the ice scientists mostly make use of radar data from satellites and planes. The radar data from dozens of satellites and research flights are combined and turned into a single, complete surface using complicated computer modelling. The most recent version of this is BedMap2, published in 2013, and includes data from research groups in the UK, EU, US, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

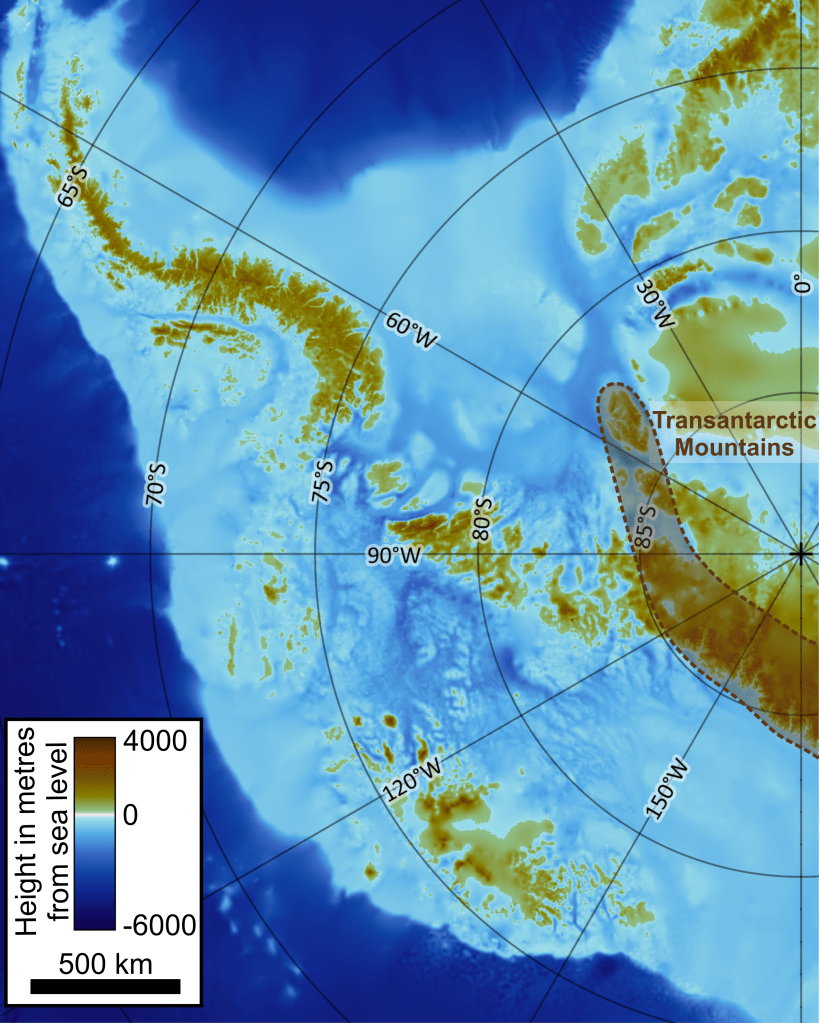

BedMap2 shows that East Antarctica is pretty standard for a continent. Underneath the centre of East Antarctica there is a mountain range that forms something like a broad plateau, cut through by the remains of river valleys that are now filled with ice. The land slopes towards the coast with higher areas inland and lower areas by the sea, which is true of most landmasses in the world.

West Antarctica, however, is almost the complete opposite. Aside from the Transantarctic Mountains and the Antarctic Peninsula, the whole western side of Antarctica is extremely low lying. In fact, most of the land in West Antarctica is well below sea level. If the ice wasn’t there it would actually be a shallow sea like the Mediterranean. Also, the highest areas of West Antarctica tend to be found around the edges of this ‘sea’, forming a chain of islands completely separate from the rest of the continent. This creates what scientists call a ‘reverse slope’ underneath the ice. It is the reverse slope which has led scientists to think West Antarctica and the WAIS are of huge importance during the current climate change.

Reverse slopes are unstable

What is a reverse slope, exactly? In terms of land shape, it is what the name suggests. The land at the coast is higher up than the land away from the coast, which is the opposite of what would be ‘normal’. The land slopes in the ‘wrong’ direction, in reverse. This kind of slope creates inland seas and lakes and is usually the result of some kind of tectonic activity.

The reason why this matters in the case of West Antarctica is because with ice sheets, the slope of the land becomes the slope at the base of the ice.

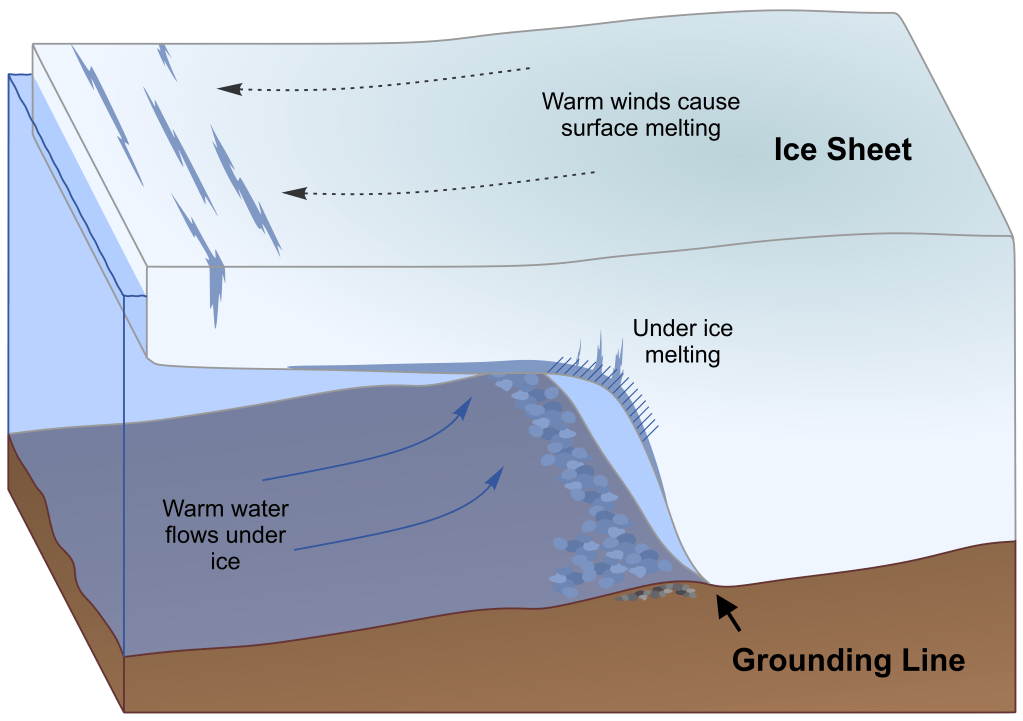

All ice sheets flow slowly from the mountains to the ocean, like rivers. At the point where an ice sheet meets the ocean, the ice starts to be pushed up by the water. Ice is buoyant, even ice hundreds of kilometres thick. Eventually the ice lifts off the ground and forms an ice shelf. This point is called the grounding line. It is the point where the ice goes from being stuck to the ground to floating.

The grounding line can tell you about how the ice sheet is doing. If it moves further out into the ocean, that means there is more ice pushing from behind. The ice is thicker and heavier and doesn’t float as easily. Usually this means the climate is getting colder or wetter and there is more snow falling onto the ice.

If the grounding line moves back, if it retreats along the slope, that means there is less ice. The ice sheet might be getting thinner because there is less snow, or there might be more melting happening. Both are symptoms of a climate that is getting warmer.

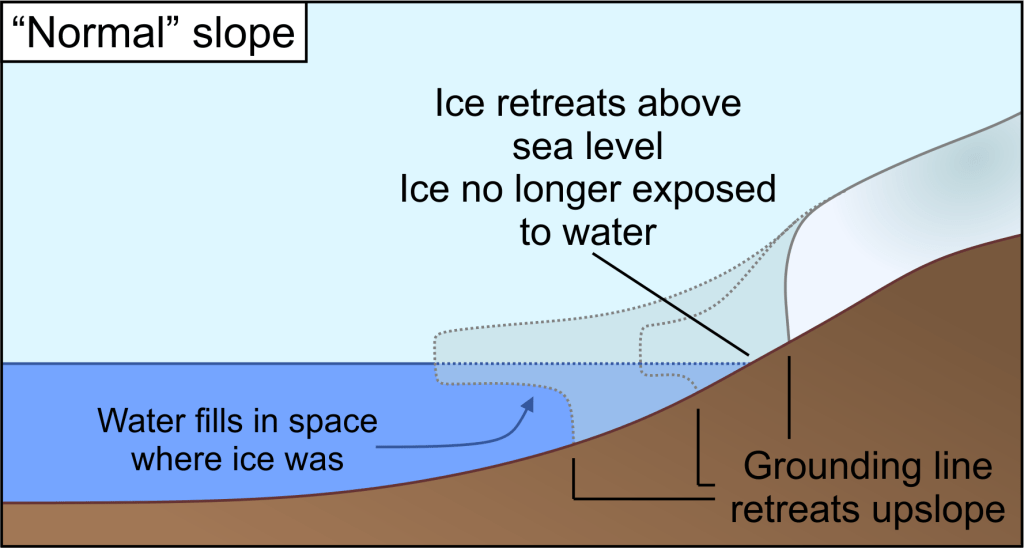

On a ‘normal’ slope if the grounding line retreats it is moving uphill. Eventually, if it retreats enough, it will move past sea level and won’t be touching the water at all. Most of the ice lost from ice sheets is lost because the ice is touching water. Water not only melts ice directly, because it is so much warmer, it also makes the ice more prone to cracking. This is how icebergs are made.

If the ice isn’t touching water, then it will lose much less ice. The retreat of the ice will slow down or even stop entirely. This is considered to be more stable, because there are ways in which the ice will stop itself from retreating further.

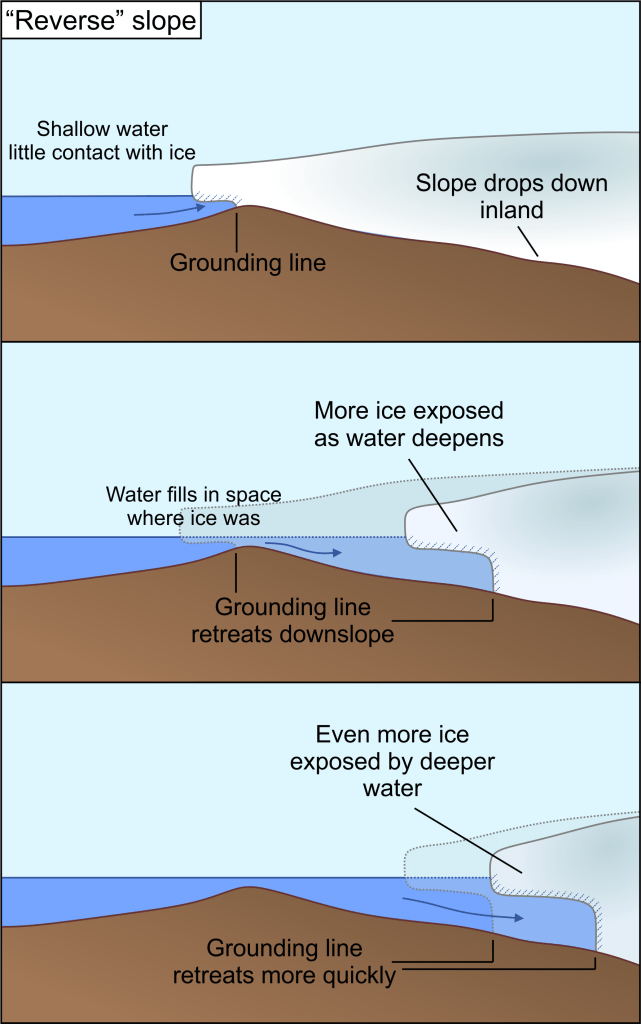

On a ‘reverse’ slope, however, it is a very different story. If the grounding line retreats downwards along a reverse slope then the water will follow. This is land that is under sea level already. All the water is doing is filling in a space that would be under water if the ice wasn’t there.

As the water fills in the space where the ice used to be, it gets deeper. Deeper water means two things: it pushes up more on the ice, meaning more ice starts to float; and it means more ice is in contact with water increasing the melting rate. Both of these things contribute to the retreat of the grounding line.

As the grounding line retreats, the water becomes even deeper. More ice starts to float and melting increases again, causing the grounding line to retreat even more.

This is what scientists call a positive feedback. Each step in the process causes the next step in a cycle that keeps repeating. Each repeat of the process gets a little faster and faster, until the cycle of grounding line retreat, increased water depth and increased melting becomes an unstoppable runaway train. Unlike a more ‘normal’ slope there is no situation in which retreat can slow down or stop until the land flattens out or starts to rise again.

Anything else that affects the thinning of ice, such as a warming climate or ice flowing faster just makes the problem worse.

What will happen to West Antarctica?

Measurements of exactly where the grounding line of an ice sheet is are difficult to get. Ice sheets are not very hospitable locations to reach and the edge of them even more so. Radar either from research flights or satellites is the easiest, but less precise.

A few expeditions have set out to the edge of an ice sheet and drilled down into the ice using hot water to find the grounding line exactly. More recently, unmanned submersibles have been sent underneath the ice shelf with precise GPS tracking to take very precise measurements of water temperature, salinity, water flow and sea bed height. The British Antarctic Survey recently released a video of the grounding line of the Thwaites glacier in West Antarctica that was captured by Britney Schmidt’s team of scientists (Schmidt et al 2023).

Although the data from these expeditions is limited because of how difficult and expensive they are to run, the pattern is consistent. The grounding lines of the WAIS are retreating and have been for a number of years.

Many of the grounding lines are currently stuck on ridges of rock underneath the ice, which are slightly higher than the rest of the sea bed. These ridges tend to pin the ice into one spot and mean the grounding line moves very slowly. In places where this sticking point has been lost then the retreat of the grounding line has become faster. If current warming trends continue, all of these pinning points will be overwhelmed. The grounding lines of the WAIS will retreat faster and faster as they move down the slope. Scientists believe that eventually the ice sheet will reach a point of no return, where there is nothing that can stop the total collapse of the ice sheet.

A collapsing ice sheet means flooding

It can be easy to dismiss the idea of a collapsed ice sheet as unimportant. No one lives in Antarctica, few people visit. Sure, it would be a loss if a third of the continent no longer had ice on it, but would it really affect anyone? After all, if you have an ice cube in a glass of water and it melts, the water level doesn’t rise. It stays the same. Would this not be the case if all the ice in West Antarctica melted away?

When looking at melting ice and sea level change, it is important to not confuse sea ice and ice sheets. Sea ice, which exists over the North Pole, floats in water. There is no land underneath. It is held up solely by the buoyancy of ice. This is your ice cube in a glass. If all the ice in the Arctic Circle were to melt, this would be a problem for polar bears, but would not significantly affect global sea level.

The majority of ice sheets, however, are not floating on water. They may have floating ice shelves as part of the ice sheet, but this is only a small portion of the total ice in the ice sheet. The rest of the ice is sat on land. Even in West Antarctica, where the land is below sea level, it is still sitting directly on a solid rock base. This means that most of the ice in the ice sheets is not displacing water.

In the ice cube analogy, the ice cube is not yet in the glass. If the ice sheet collapses, it is the moment when the ice cube is added to the glass, not when it melts away. If you add an ice cube to a glass of water, the water level goes up.

The WAIS contains enough freshwater to raise sea levels by 3.5 metres. This might not seem like a lot, but it is estimated over 250 million people live within 2 m of sea level. If sea levels rise by that much then all of those people will be forced to relocate simply because their homes are now underwater. Flood defences are an option, true, but only if you can afford them. They can also only do so much. No engineering we currently have can hold back the ocean indefinitely.

Islands are particularly at risk from rising sea levels, because they tend to be very low lying. The Solomon Islands in the Pacific, north-east of Australia have already seen islands drowned by rising sea levels. The Bahamas, Maldives, Fiji and many others across the globe are trying to mitigate the effect of rising sea level to protect their populations and way of life.

If it reaches the tipping point, scientists think the WAIS could collapse entirely within 50-100 years. However, the sea level rise will start long before that, in fact it has already begun. As grounding lines retreat around West Antarctica, ice that was previously sat on land is now floating. The ice cubes are slowly being added.

A collapse will be permanent

The biggest questions around West Antarctica right now isn’t ‘will it collapse’ but ‘when will it collapse’ and ‘how much will collapse’? Scientists know that the point of no return is fast approaching for many of West Antarctica’s glaciers. From there, it won’t take much more warming for the whole ice sheet to reach breaking point. If we can limit warming we might be able to save some of the WAIS, but how much still remains very uncertain.

If the WAIS does collapse, this is effectively irreversible. It may only take 100 years for an ice sheet to collapse, but it takes thousands, even tens of thousands for it to form. The associated sea level rise is therefore also permanent and will change the shape of our coastlines forever.

It may seem like the use of terms like ‘doomsday’ and ‘catastrophe’ and ‘irreversible collapse’ are overused when it comes to West Antarctica. In the modern day of turning every news piece into a disaster, it is easy to think that these stories are over-exaggerated for the drama. The truth is, however, that for once the news is spot on.

The collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would be a global disaster driving hundreds of millions of people from their homes. It is a collapse that we might not be able to stop in time. The collapse won’t happen overnight. It may take 50 years or it may take 100. However, the sea level rise it will cause has already started. More ice cubes are being added to the glass, at some point it will start to overflow and by then, it will already be too late.

Leave a comment